Chapter 2 Connecting Home Prices to Voting

We’re creating…an ownership society in this country, where more Americans than ever will be able to open up their door where they live and say, welcome to my house, welcome to my piece of property.

The Housing and Economic Recovery Act (HERA) countered the foreclosure crisis with a ream of policies aimed at mitigating spillover effects of the subprime mortgage crisis. At first glance, these policies are nothing more than containment measures to halt the spread of foreclosure and dislocation. While HERA was that, it was much more. A product of contentious debate on the House floor (the bill faced 17 different roll call votes on its route to the President’s desk62 Pelosi, “HERA.”), HERA reflected a cacophony of political voices. While federal legislation is more a product of compromise than parliamentary legislation, American laws can be decomposed into smaller titles and programs that closer reflect the wills of particular caucuses or politicians.63 It is this by this characteristic that individual amendments are labeled as “pork-barrel politics”.

In this spirit I try to isolate the partisan content of the Neighborhood Stabilization Program in the hope of conveying how the NSP as a concept may have presented to a voter. To do so, I plumb the recent history of subprime housing and the centering of tax policy in Republican platforms. I find that slotting the NSP unambiguously into one party’s platform is difficult: while housing was a large-scale tool used by every president from Reagan to George W. Bush, it was not part of most political debates. The housing programs created out of the Great Depression were largely directed from the executive branch, while state- and local-level programs lacked the legal authority, financial power, or political base to be anywhere near as effective. Because of the distinctly presidential flavor of housing, it was largely excluded from the kind of multilevel alignment that has shaped, say, gun policy. Nonetheless, this legislative and executive history presents an important prologue to the further politicization of taxes, welfare, and housing subsidies by the Tea Party. It explains how actors responded to political stimuli with policies that created the large-scale system of subprime borrowing that triggered so many of the events detailed in Section 1.1.

In this chapter, I dive into how the Neighborhood Stabilization Program fit ideologically with the Bush administration and Republican Party between 2008 and 2010. I argue that though the NSP fit within the Bush administration’s housing policies, it nonetheless hewed more closely to the ideology of the Democratic Party than that of the Republican Party between 2008 and 2010. This ideological fit was not a given, but was contingent on a tax protest movement like that of the Tea Party, which sprouted from the same anti-tax stems that yielded the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Followed by George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, Reagan began a new type of housing policy that tied it to an increasingly-large financial system. The same politics that set in motion the largess of subprime were integral to corralling the effects of foreclosure relief programs into meaningful political distinctions. With such distinctions, candidates could then represent the preferences that I will explain in Chapter 3.

2.1 The Neighborhood Stabilization Program, Ideologically

Despite the ideological congruence between the NSP and Bush’s ownership society, the Neighborhood Stabilization Program was at odds with the Republican Party ideologically by privatizing government money for less (or even negatively) wealthy people. Both Republican and Democratic parties have connected programs that transfer taxpayer money to less affluent people with higher taxation, and with the post–New Deal Democratic Party.64 Schwartz and Seabrooke, The Politics of Housing Booms and Busts, 212. So, while the policies fit with the Bush administration, they resembled proposals from the left. Simply put, recipients might tend to recognize the Neighborhood Stabilization Program as a product of the Democratic Party, and vote accordingly in a you-scratch-my-back-I-scratch-yours type of way. However, identifying the NSP as a Democratic policy would be at tension with the conservatizing effects of rising wealth. The collision of these two effects—one ideological, the other financially rational—has not yet been studied, a fact I hope to remedy by analyzing voting returns in Section 4.3.2.

Section 2301(a) of the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 appropriates $3,920,000,000

for assistance to States and units of general local government (as such terms are defined in section 102 of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 (42 U.S.C. 5302)) for the redevelopment of abandoned and foreclosed upon homes and residential properties.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) administered the funds through its Community Development Block Grant program, a core piece of HUD’s community investment apparatus. By routing the funding through a pre-existing program, the bill’s writers sought to leverage established lines of administration between HUD and the several states. This provision also avoided long-term commitments by HUD to far-flung localities, pushing the purchase and selling of properties to an arms-length. But, while the bill collected information and decision-making at the local level, its compliance regulations were still onerous. Immergluck argues that ensuing language in HERA, which limited localities to purchase properties at a discount from market price, lessened the program’s efficacy. Much like with the market for used cars, houses at a discount are always already more likely to be lemons, since the seller wouldn’t take less than market price for an above-average quality home. Beyond that, federal oversight of localities was intense, as the administration took an extremely risk-averse approach to mismanagement of funds, fitting the image pushed by conservatives in Bush’s party of housing programs as loci of graft and inefficiency.65 Daniel Immergluck, Preventing the Next Mortgage Crisis: The Meltdown, the Federal Response, and the Future of Housing in America (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2015).

Funds were originally calculated by a need-based formula factoring in rates of foreclosure, subprime borrowing, and payment delinquency in order to address areas “identified by the State or unit of general local government as likely to face a significant rise in the rate of home foreclosures.”66 Pelosi, “HERA.” In doing so, the legislation aimed to use the buying power of the federal government to bid up prices in neighborhoods by taking housing stock off the market (reducing supply), recording purchase prices close to market levels (benchmarking nearby appraisals and sales), and reselling said housing stock after maintenance and repairs (increasing quality).

But the political import of this plan is difficult to understand in the vacuum of its administration and guiding legislation. Due to the size of the bill passed and the extent of modifications, it is unclear who inserted the provision. But at the time, dispossessed homeowners and their coalitions called for principal reductions, a common decision in courts of equity and bankruptcy cases, or immediate relief to homeowners currently in default. A select few news sources picked up on the insertion, including a Reuters piece which claimed “The White House had originally opposed a provision that offers $4 billion in grants to states to buy and repair foreclosed homes.”67 Jeremy Pelofsky, “Bush Signs Housing Bill as Fannie Mae Grows,” Reuters, July 2008. The opposition by the Bush administration of the $4 billion outlay, a mere 1.3% of the $300 billion ensured to Fannie Mae, indicates that the amender likely belonged to the Democratic Party. Albeit brief, this opposition—the only opposition mentioned in an article awash in hundred-billion-dollar outlays—is surprising since its aim ran parallel with the Bush administration’s “ownership society”, a doctrine which added moral heft to the legal responsibilities associated with private property. By mitigating spillover effects, the Neighborhood Stabilization Program would cosset homes from the “animal spirits”68 Keynes and Krugman, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. of tumultuous housing markets and ensure that the success or failure of a person’s finances depended on their own actions.

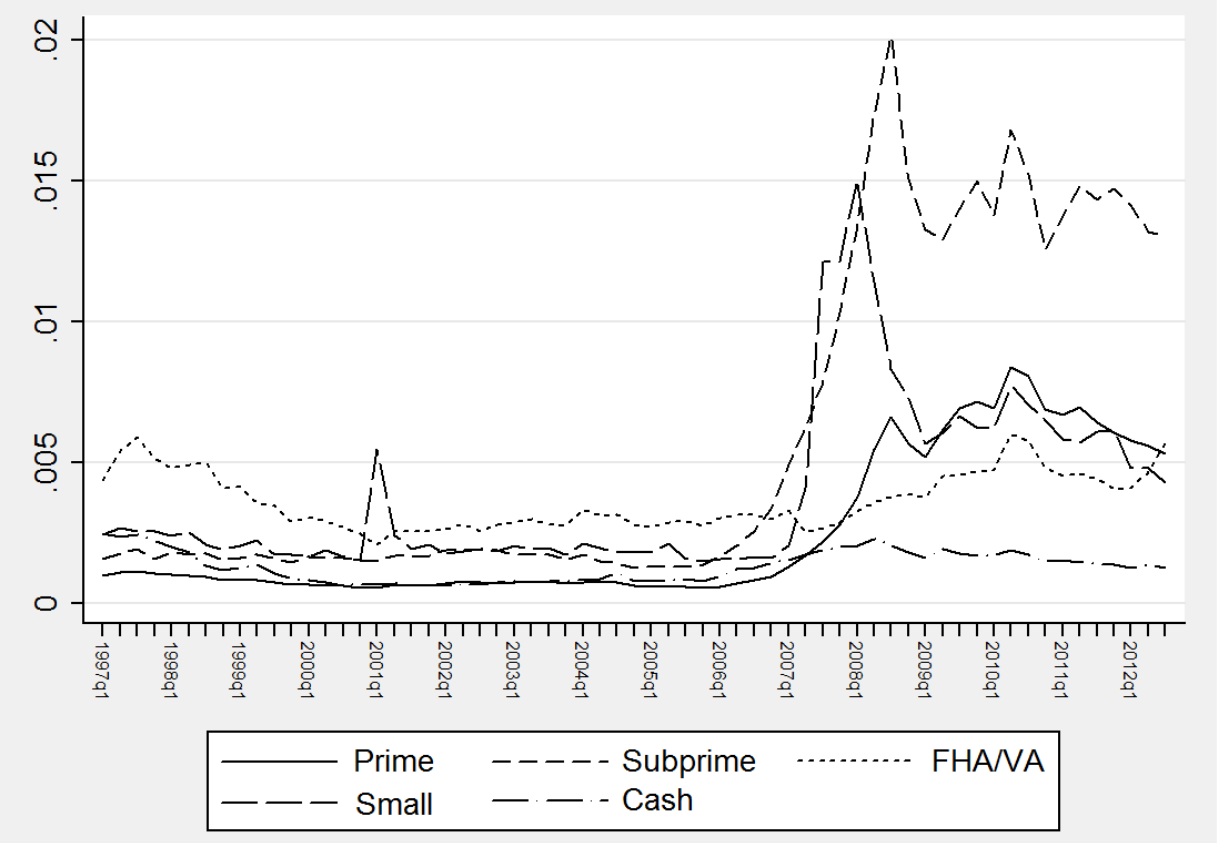

Figure 2.1: Probability of home loss by owner type. The lag between subprime and prime was partially because there was more ‘fuel left to burn’ in the sense that the number of subprime borrowers, already only 20% of the market, had already been slashed.

Figure 2.1: Probability of home loss by owner type. The lag between subprime and prime was partially because there was more ‘fuel left to burn’ in the sense that the number of subprime borrowers, already only 20% of the market, had already been slashed.

And, rather than using direct cash transfers—which would have enhanced individual freedom by loosening household budget constraints—or pass-through payments to debt holders—which would have promoted rent-seeking by those debt holders—the Neighborhood Stabilization Program advocated for indirect bumps on home equity. The administration took larger-than-usual measures to distance itself from political (and legal) liability. The necessity of these measures is questionable: while 45% of Sand State mortgages issued in 2006 were for second, third, or fourth properties,69 Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, “House Prices, Home Equity-Based Borrowing, and the US Household Leverage Crisis,” American Economic Review 101, no. 5 (August 2011): 2150, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.5.2132. it is important to remember that the majority of those foreclosed upon were prime borrowers. Further, the distress of prime borrowers came somewhat after that of subprime borrowers, as seen in Figure 2.1, taken from Fernando Ferreira and Joseph Gyourko.70 “A New Look at the U.S. Foreclosure Crisis: Panel Data Evidence of Prime and Subprime Borrowers from 1997 to 2012,” Working Paper (National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2015), https://doi.org/10.3386/w21261. These facts suggest that neighborhoods with prime borrowers contracted the foreclosure contagion from subprime borrowers, which seems, 12 years later, to be proximately true.71 Tooze, Crashed; Atif Mian, Amir Sufi, and Francesco Trebbi, “The Political Economy of the US Mortgage Default Crisis,” American Economic Review 100, no. 5 (December 2010): 1967–98, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.5.1967. Rather than prudent oversight, the Bush administration responded to the political stimulus provided by Rick Santelli (among others), who fingered corner-cutting subprime homeowners for forcing their responsible, well-to-do homeowners into foreclosure, rather than their collective panic, lax credit markets, or negligent mortgage brokering.

The administration sought to maintain the idea of a meritocratic path to the American Dream, while trying to avoid acknowledging that, every so often, such a route must be cleared of hazards. The Neighborhood Stabilization Program did not aim, like its administrative superstructure does, to develop communities in any meaningful way. Rescuing communities from visual blight were incidental effects of the policy and tied only to blight’s impact on home prices. Rather, the NSP aimed at the more foundational goal of saving the plunging home equities of several million individuals.

This individuation, this buffer from the market, is a privilege long constructed for the American home by law and policy. Specifically, the private-public distinction is made much sharper for homeowners than for renters. Consider for instance 4th Amendment cases, where [English] property law still dominates legal interpretation (despite the impact of Katz v. United States, which expanded what the 4th Amendment shielded to include more person-centric concepts).72 Stephanie M. Stern, “The Inviolate Home: Housing Exceptionalism in the Fourth Amendment,” Cornell Law Review 95 (May 2010): 48. Or consider the mortgage interest deduction, a large subsidy applied to owner-occupied properties often considered part of the “hidden welfare state.”73 Christopher Howard, The Hidden Welfare State: Tax Expenditures and Social Policy in the United States, Princeton Studies in American Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1997). The history of American housing policy—both as centralized legislation and decentralized legal interpretation—has conferred on homeowners (who, in the case of single-family housing, are also land owners) additional rights when compared to renters, expanding the legal extent of their individual selves.

These privileges made up much of the popular appeal of George W. Bush’s “ownership society”. While it lived a larger life in the media than in Bush’s own remarks, the philosophy can explain much of Bush’s domestic policy, and should therefore be taken seriously. The definition is almost self-evident: an America where as much is owned and controlled by individuals as is feasible. Bush explained the logic guiding this idea by claiming that “The more ownership there is in America, the more vitality there is in America, and the more people have a vital stake in the future of this country.”74 “Fact Sheet: America’s Ownership Society: Expanding Opportunities,” Archive, The White House: President George W. Bush (https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2004/08/20040809-9.html, August 2004). With this claim came a scaffolding of policies constituting the promise of an model ownership society.

Under this capacious roof, the administration housed health savings accounts, more individuated retirement options, and policies aimed at boosting homeownership.75 Naomi Klein, “Disowned by the Ownership Society,” The Nation, February 2008. These policies included the American Dream Downpayment Initiative (fairly self-explanatory) and the Single-Family Affordable Housing Tax Credit.76 “Homeownership Policy Book - Chapter 1,” Archive, The White House: President George W. Bush (https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/homeownership/homeownership-policy-book-ch1.html, 2002). By encouraging single-family homes in the “Nation’s inner cities”, thinning the density of apartment complexes and tenements, this last provision hearkened back to New Deal marketing, which idealized the home as a Romantic “refuge from urban corruption”77 Stern, “The Inviolate Home,” 910. associated with a high-density cityscape and the web of problems spun around public housing complexes. Bush’s ownership society provisions also included a “tripling of funding”78 “Homeownership Policy Book.” for a program that swapped personal or volunteer labor for housing assistance, known in low-income housing development as “sweat equity”. These programs in aggregate, pushed a narrative of meritocratic access to consumer credit spurring individual ownership.

The benefits extended to Latinx borrowers. In 2005, the Bush administration chose not to extend regulations over non-FDIC lenders that supplied minority borrowers in an effort to quash Democratic gains in the Southwest. Karl Rove, in fact, claimed that homeownership could economically conservatize Black and Latinx voters. The 9% drop in Democratic share of Latinx voting between 2000 and 2004 may be partially attributable to the 2.8% spike in homeownership in that time.79 Herman M. Schwartz, “The Politics of Housing Provision and Property Bubbles in the United States and Europe” (Book Chapter, January 2018). But since all this movement occurred at the level of the executive, and the implications of easy mortgage credit seemed not to be picked up by politicians outside Florida, a distance sustained between Republican rhetoric and the de facto party policy led by the Bush administration.

The NSP slotted into Bush’s story by insulating responsible (i.e. those who have not yet defaulted) debtors from wily housing markets. Such a conformity with both Bush’s animating philosophy and with Democratic pushes to expand access to homes80 Tooze, Crashed, 47. places the Neighborhood Stabilization Program in murky territory with regard to party affiliation. If voters were unable to locate programs like the NSP within distinctly Democratic or Republican platforms, then there would be no clear reason why pro–home price policies translate into Republican votes. But while the values cherished by Bush’s ownership society aligned ideologically with American conservatism, its distinctive policies were afield of the Republican platform. Part of this separation was because Bush’s ownership society was not too different than the messages had pushed by presidents on both sides of the aisle since at least the Great Depression.81 Stoller, “The Housing Crash and the End of American Citizenship.” Rather, the policies looked like a [more] moralistic version of Democratic plans for affordable housing and access to credit.

2.2 Shifting Priorities in the Grand Old Party

Republican antipathy to taxation and opposition to continuing welfare assistance crowded out other domestic policy issues, like the politics of debt that had been so visible to Midwest farmers in the 1930s, Massachusetts farmers in the 1780s, and opponents of the Cross of Gold in the late 19th century. Instead, what talk there was regarding debt resulted from a more general concern over asset prices. This talk proceeded from the expansion of finance’s place in the economy and culture of the United States. While bankers had always been handsomely paid, it was not until the liberalizations of the Reagan era that its ranks swelled in quantity and individual wealth. These included passage of the Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982—which Paul Krugman held responsible for the savings and loan crisis (if not for the macroeconomic factors that initially stressed S&Ls) by granting permission to private lenders for the sale of adjustable-rate mortgages82 Paul Krugman, “Reagan Did It,” The New York Times, May 2009.—but I pay particular attention to the exaltation of multinational creditors in mortgage markets. A year before the Garn–St. Germain Act, Reagan enacted his signature reform, the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, which allowed troubled savings and loan institutions to sell home mortgages and consequently write down their tax burdens.83 Michael Lewis, “The Fat Men and Their Marvelous Money Machine,” in Liar’s Poker (W.W. Norton & Company, 2010). This provision opened the floodgates for private-label mortgage securitization; where savings and loans had dominated the private market, investment banks could now cash in. By definition, it was these creditors that enabled the expansion of mortgage-backed securities to subprime lenders, and with them, significant economic growth.

Between 1981 and 2007, outstanding residential mortgage debt—shown in Figure 2.2—swelled from 37% of US gross domestic product to 82%, more than doubling in relative size.84 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), “Mortgage Debt Outstanding by Type of Property: Farm,” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MDOTPFP, October 1949); Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), “Mortgage Debt Outstanding by Type of Property: Nonfarm and Nonresidential,” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MDOTPNNRP, October 1949); Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), “Mortgage Debt Outstanding, All Holders,” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MDOAH, October 1949); U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Gross Domestic Product,” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPA, January 1929). On the other side of the largest pool of consumer debt in the world stood an even larger pool of capital. While the rampant foreign direct investment (FDI) of Japan and Germany are often noted in economic histories of the 1980s, potentially more significant were the destination of such capital flows. Herman Schwartz disaggregates the flows of FDI entering and exiting the United States to explain why, despite the large net debt position of America, the country was not hamstrung by austerity provisions but actually received net positive income. His answer is that the consumption-driven American economy leveraged the credit made cheap by global disinflation to extend its own resources and drive aggregate demand.85 Schwartz, Subprime Nation. Global disinflation resulted partially from the sheer supply of credit, in turn making the interest rates offered by US mortgage-backed securities a viable alternative to dampening rates of return on traditional investments. This process fueled itself for a while: lower interest rates meant that buyers could afford more expensive homes on the same monthly payments, bidding up the prices of homes; when nearby home prices appreciated, homeowners could refinance, paying off the first mortgage, marginally lowering the risk and thus interest rate for the next mortgagee in the market. This process played out in every country able to profitably securitize mortgages, but the Reagan administration’s reconfiguration of credit enabled the United States to reap the world’s largest benefits—Schwartz credits this system with driving the United States’ differential growth above the rich Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries between 1991 and 2005.86 Schwartz, 4. Adam Tooze credits Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan pushing the levers of housing most opportunistically, explaining how he plunged interest rates to 1% following 9/11 and the Dot-com crash to entice homeowners to refinance.87 Tooze, Crashed, 55.

Figure 2.2: Outstanding US residential mortgage debt as a percentage of US gross domestic product.

More than good macroeconomic policy, the growth buffered homeowners from wage stagnation or job loss altogether. In conjunction with liberalized finance, norms and regulations were repealed that had protected the Fordist labor compact linking secure employment with secure mortgages. While these repeals have wrought havoc on bargaining power, their perceived impact was aided—and perhaps eclipsed—by the spatial and international movements of manufacturing jobs away from the organized mid-Atlantic and Midwest, to the unorganized American South, and ultimately to the Global South. In any case, labor markets became increasingly volatile in the United States, necessitating some form of insurance. Matt Stoller argues that the exaltation of finance, subordination of labor, and mitigation of social insurance policies can be viewed macrosocially as a renegotiation of the American social contract inaugurated by the New Deal.88 Stoller, “The Housing Crash and the End of American Citizenship.” Where businesses had profited on the aggregate demand generated by collectively-bargained salaries and the commensurate long-term commitments by employer and employee, the new asset-backed political economy dampened the need for stable, steadily increasing salaries, replacing labor gains with capital gains. These jobs, salaries, and benefits then acted as dragnets on profits, ultimately to be jettisoned at the behest of shareholders. In return, the asset-backed social contract offered cheap credit and the Minskyan promise of speculative returns to supplement, or supplant, income.

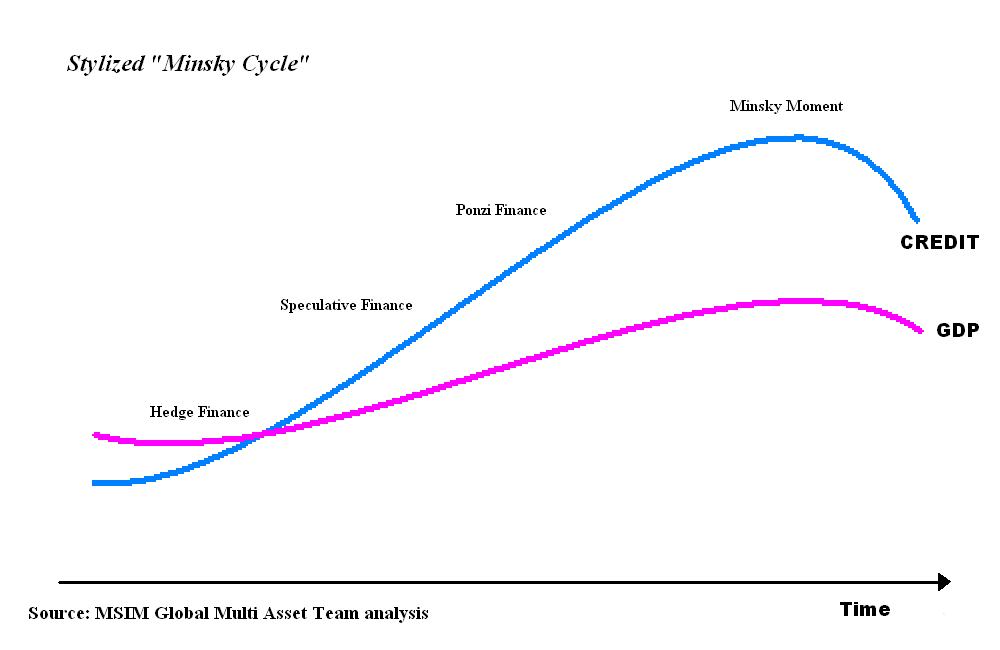

Figure 2.3: A cycle of speculative finance theorized by Hyman Minsky.

Figure 2.3: A cycle of speculative finance theorized by Hyman Minsky.

By locating this process in the Reagan administration, I have obviously extended beyond my self-imposed 1991 start date for continually-increasing home prices. The point I make here is that the infrastructure for that incredibly-long price surge was built a decade before. Then, in the 1990s, the endogenous ability of speculative home buying ramped up. I point to somewhere in the middle of the 1990s, when homeownership soared, as an inflection point in the Minsky cycle (pictured in Figure 2.3) between speculative and Ponzi financing, a point before which home building and buying was foundational to this new “social contract” but still directly dependent on the income swings and employment patterns of millions rather than on speculation nearby.

Despite 1991’s brief negative sojourn, this social contract contingent on rising home prices was leveraged by Bush the elder as well as Bill Clinton in their presidencies. Housing, often couched in the language of the American Dream, garnered vaguely bipartisan support at the national level: while there were differences between Republican and Democratic housing policies, their approaches were united by a vocabulary of taxation and credit, not debt. Despite the rich history of debt politics among American farmers, parties focused on expanding access to credit and limiting the toll to government expenditures, rather than limiting the burden of debt and expanding government revenues.

To be sure, this vocabulary constituted a rational response—so long as markets showed signs of growth, debt relief would be a minor issue, while tax reductions and access to credit extended individual budgets. But it was not uniquely rational: dependable debt relief could, if annualized, be indistinguishable from a similarly-sized mortgage tax credit; after all, with all the easy credit, there was certainly enough debt to go around—in addition to mortgage debt equaling 82% of gross domestic product, mortgage debt service payments in 2007 increased 75% over 1981 levels.89 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), “Mortgage Debt Service Payments as a Percent of Disposable Personal Income,” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MDSP, January 1980).

To summarize, the Neighborhood Stabilization Program sought to insulate homeowners from the market by using the buying power of the federal government to fix local home prices. This program, despite the initial opposition of the Bush administration, fit with George W. Bush’s “ownership society”, which emphasized private, family-owned property as both a social and economic doctrine. But Bush’s ownership society, while conservative, helped established and would-be homeowners manage and mitigate their debt load. This practice, however, focused in the executive branch, and so was not politicized by Republicans in the legislature or in states.

2.2.1 The Centering of Tax Policy

It was not that the NSP completely contradicted the Grand Old Party, but rather that policies affecting housing debt (and wealth) were outside the scope of national rhetoric; debt was illegible to Republican voters. Instead, Republicans cast housing debt—and programs that help homeowners pay down housing debt—as a burden to the tax base. But why, and how, was a question of debt transfigured into one of taxation? Answering this question offers more than colorful background; understanding how tax and debt politics fall contingently into particular parties (or out of the mainstream altogether) bridges the gap between rational choice preferences and Congressional representative voting outcomes. My answer also connects taxes with expenditures, a non-trivial connection that will become very important when individual preferences for social insurance are considered in the next chapter.

I argue that the tax “revolts” kicked off by Proposition 13 in California brought to the fore the question of taxes. Reagan’s presidential campaign then finalized the centering of taxation in Republican domestic policy. By centering taxation—and succeeding politically in implementing favored tax cuts—the Republican Party led voters to expect tax cuts and trained taxpayers to see themselves as a political class. With taxation in the center, and Democrats playing a softer version of Republicans’ tune, debt politics became illegible as politics, rendering any small resurgence into a social movement.

Despite some notable tax activism (see: Boston Tea Party), Americans were generally quiet about taxes well into the 20th century. This phenomenon was no doubt largely because the federal income tax fell on no one until 1913, and less than six percent of the United States population until 1940.90 “Historical Sources of Income and Tax Items,” Tax Policy Center (https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/historical-sources-income-and-tax-items, October 2019). But after that point, the direction of tax expenditures—towards national defense in the beginning of the Cold War and for New Deal welfare programs such as the Social Security Act—were popular enough to discourage politicians from taking aim at tax cuts.91 Andrea Louise Campbell, “How Americans Think About Taxes: Lessons from the History of Tax Attitudes,” Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association 102 (2009): 160. This equilibrium continued until the 1960s. The fiscally-conservative Southern Democrats who controlled Congress’ tax-writing committees92 Campbell, 162. were then voted out of office or changed party allegiances following federal enforcement of Civil Rights Movement legal judgments (such as Brown v. Board of Education), the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting acts, and finally Nixon’s Southern Strategy in the 1970s.

Then, in 1978, Californians voted in favor of Proposition 13, which limited the property tax rate to 1%. Proposition 13 emerged out of a long-fought battle by tax activists against the rationalization and modernization of property tax assessment.93 Isaac William Martin, “Welcome to the Tax Cutting Party: How the Tax Revolt Transformed Republican Politics,” in The Permanent Tax Revolt: How the Property Tax Transformed American Politics (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008), 126–45. Tax assessors declined to re-appraise property values at common intervals, leading to “fractional assessment” that, in 1971, “was ten times greater than the home mortgage interest deduction,”94 Martin, 9. mentioned above as a quintessentially bourgeois example of the relatively-regressive American tax policies. The success of Proposition 13 realized the potential of anti-tax movements in post-war, post–New Deal American politics. Interviews of Congressional staffers at the time referred to a ‘Proposition 13 mentality’95 John W Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (New York: Longman, 1995), 97. and President Jimmy Carter said the result “sent a shock wave through the consciousness of every public servant.”96 Howard Jarvis and Robert Pack, I’m Mad as Hell: The Exclusive Story of the Tax Revolt and Its Leader (Times Books, 1979), 3. Interestingly, Proposition 13 was not destined for the Republican platform from the outset. Isaac William Martin refutes this perception by noting the colorful array of leftists, hippies, anti-government organizers, and 9-to-5-ers that marched in the streets in support of the referendum, while President Carter’s comment above highlights the immediacy with which Democrats understood Proposition 13’s political effects. Rather, it was Reagan’s signature income tax cuts that assimilated the anti-tax fervor to the Republican platform.

It is important to note now how my argument has developed with respect to a theory of political change. In Section 1.2.1, I briefly engaged farmer activism in the Great Depression, a mass movement that saw thousands pack courthouses and politicians’ offices. Here, I make a slight turn: while again activism prompted radical shifts in policy, the Republican turn did not feature near-intimidation tactics, nor did “an astonishing array of antediluvian automobiles [… swarm] over the capitol.”97 Fliter and Hoff, Fighting Foreclosure. The tax revolt “did not change what most people thought about taxes, [but] it did change how much the major parties paid attention to taxes.”98 Martin, “Welcome to the Tax Cutting Party,” 127. Emphasis Martin. This transformation moves closer to accounting for political change in the choices of elite actors than my history of the mortgage moratoria, but it still found its roots in grass. The next movements are much different; they see political strategists and small, connected groups of activists introduce citizens to ever more radical suggestions. I understand this shift as taking place in a moment of transition: when there suddenly opens unsettled ground to be claimed, it is political elites who decide what flag it will fly. The ground was unsettled in the sense that the partisan coding of anti-tax policies was ambiguous—the two parties had converged more or less—where Democrats had backed debt politics before the mortgage moratoria.

In the final centering of tax policy on the national level, Ronald Reagan would be the agent of change. The explosive success of Proposition 13 changed Reagan’s mind on taxes. Before, he had been convinced that tax limits would just shift the burden of taxation onto one of its other forms in personal or corporate taxation.99 Martin, 129. This belief came from a connection made between revenue and expenditure, a logic of reaping what one sows. In California, however, local governments did not collapse, and what changes did occur to the provision of social services evidently did not summon a pro-tax backlash; in other words, “you could cut taxes deeply without worrying about deficits.”100 Martin, 130. The reality about this de-coupling is very important to my argument. There have always been large chunks of discretionary spending that could be trimmed. Yet, the focus of balancing the deficit rarely falls (and rarely fell) on the most massive chunk, military spending. The purported want to balance budgets—echoed by every recent president—does not imply a need to contain visible (or invisible) welfare programs and transfers to local governments. Rather, it is by political construction that programs like the Neighborhood Stabilization Program end up in budget debates.

Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign picked up on the Proposition 13 rhetoric, mentioning taxes in more times than any previous candidate had in his nomination acceptance speech.101 Andrea Louise Campbell, “What Americans Think of Taxes,” in The New Fiscal Sociology, ed. Isaac William Martin, Ajay K. Mehrotra, and Monica Prasad (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 48–67, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511627071.004. He offered tax cuts within a larger theory, connecting the private economic conditions with larger social problems. These would respond, not to the popular New Deal provisions, but to the increases in expenditure brought by Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, not yet 20 years old. Taxes were certainly not the only issue on Reagan’s platform, but they are that for which he is remembered: the Iranian hostage situation and antidote to Jimmy Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” sermon were contingencies where taxes were a certainty. His signature tax cut—the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 that spurred savings and loan banks to sell off mortgages—was not so popular when enacted, but it became a key feature of his popularity as the economy rebounded before the 1984 presidential election and has lingered in his public image.102 Brett Robert, “‘Reaganomics’: The Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981,” The Reagan Library Education Blog (https://reagan.blogs.archives.gov/2016/08/15/reaganomics-the-economic-recovery-tax-act-of-1981/, August 2016).

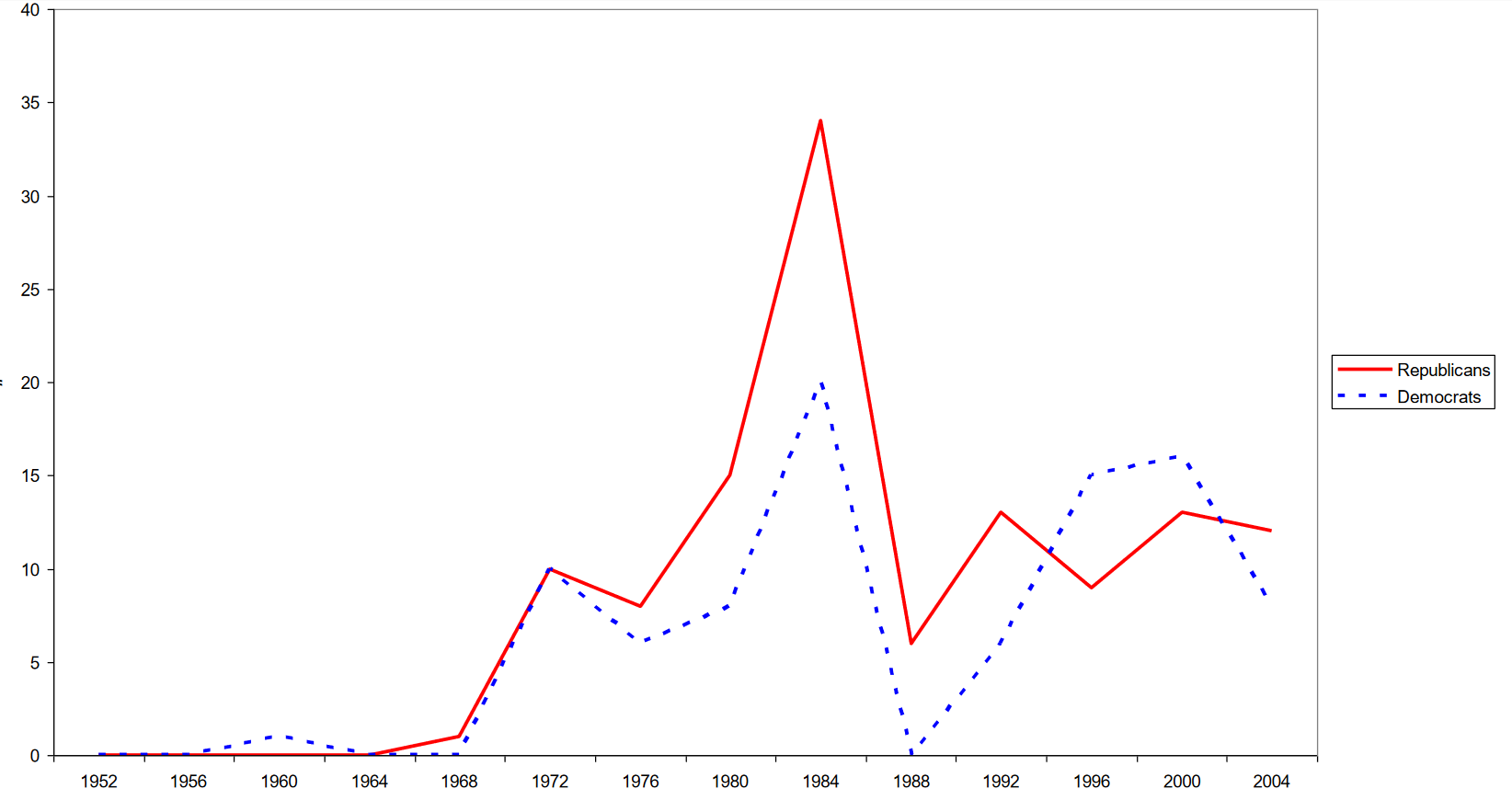

Figure 2.4: Number of tax mentions by party in presidential nomination acceptance speeches.

Figure 2.4: Number of tax mentions by party in presidential nomination acceptance speeches.

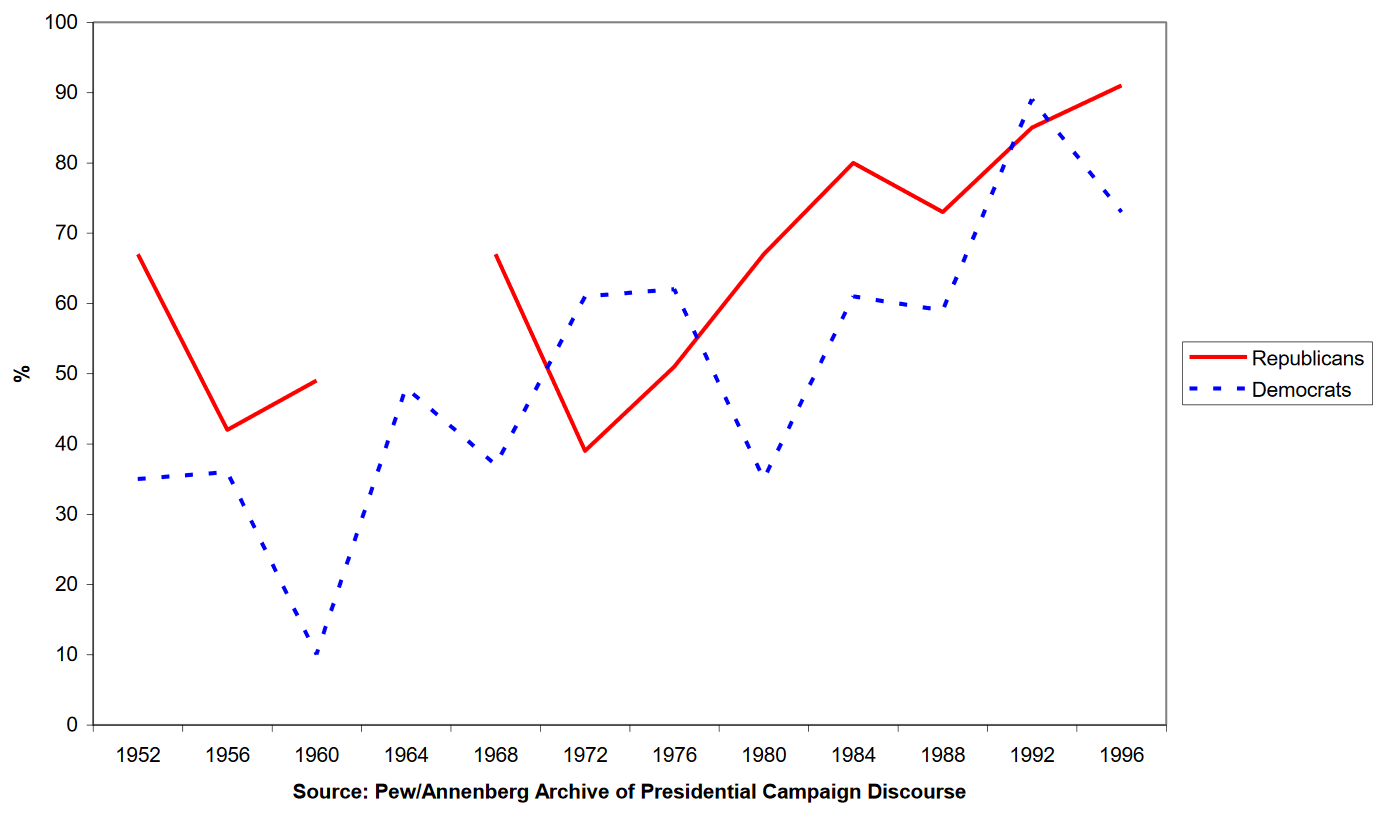

Figure 2.5: Percentage of general election TV ads to feature taxation, by party.

Figure 2.5: Percentage of general election TV ads to feature taxation, by party.

After the reforms of the first term, the campaign ramped up its tax rhetoric. Figure 2.4 shows the massive spike in tax mentions in nomination acceptance speeches. Figure 2.5 meanwhile shows a similar spike of mentions in general election television ads aligning with the 1984 election. Bolstered by the knowledge that one could uncouple taxes from spending, Reagan was able to fend off Democratic challenger Walter Mondale’s criticism that, “Reagan will raise taxes and so will I. He won’t tell you.”103 Howell Raines, “Party Nominates Rep. Ferraro; Mondale, in Acceptance, Vows Fair Policies and Deficit Cut,” The New York Times, July 1984, 1. Ronald Reagan would go on to win every state except Minnesota, Mondale’s home.

After Ronald Reagan, it was the House Republicans who fueled the drive towards lower taxes. Isaac William Martin takes over here:

Gingrich derided [balanced-budget Republicans’] argument for tax increases as an “automatic, old-time Republican answer.” He thereby implied that the new Republican answer was to cut taxes even when there was a deficit. After President Reagan signed tax increases in 1982 and 1983, Gingrich was instrumental in rewriting the Republican Party platform in 1984 to repudiate further tax increases. In 1990, he broke ranks with President George H. W. Bush and led House Republicans in voting down the president’s budget—because it included a tax increase.104 Martin, “Welcome to the Tax Cutting Party,” 133.

I dwelt on Ronald Reagan’s tenure because it was an inflection point in national politics. The breakdown of Fordism in the United States, and its replacement by asset-backed political economy, was aided by Reagan’s policies. In contrast, the crystallization of taxation as dominant Republican issue, while crucial to telling the story of how past became present, is less important to understanding how housing and taxation function conceptually in American politics.

As such, I will race through Clinton’s presidency with equal pace. Notable in the Campbell graphs are the mentions of taxation by Democrats in the Clinton era. So, while Gingrich drove legislation such as the Contract with America and the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act through Congress, it was not he—nor Republicans—alone. In addition, Clinton co-opted what had been Republican positions on welfare, and his labeling as a Third Way or New Democrat can be seen as trying to distance his politics from those of the party generally. Clinton’s focus on budget balance differed from what Reagan and Gingrich had pushed, re-coupling revenue with expenditure, but the expenditure in focus was (as always) welfare. By “end[ing] welfare as we know it,” Clinton coupled preference for social insurance with preference for higher taxes. After Clinton, the presidential campaigns of Barack Obama and John Kerry would return Democratic campaigns to emphasizing the need for higher taxes and more supportive (visible) welfare programs.

Following Isaac William Martin’s argument about the importance of Proposition 13, I have argued that tax activism propelled Republican victories in the 1980s. Successive legislative and electoral efforts would then de-couple taxes from government spending, leaving a narrow set of discretionary spending over which candidates and legislators could argue. This set emphasized visible welfare programs (such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) that socialized insurance across the tax base. By centering taxes in the national conversation, individual debt politics became increasingly illegible to voters. Additionally, the connection between welfare spending and taxes meant that those who felt secure financially would opt to keep otherwise-taxed income instead of the social insurance policies those funds were supposedly directed towards. The connection between spending and taxation, however, fades from view somewhat in the early 21st century, as massive funds are appropriated for the War on Terror while Bush’s first tax cuts remain deep. Reconnecting those threads were the work of anti-tax organizations and their allies in Congress, with Obama’s emergency stimulus packages offering the opportunity of a political career.

2.2.2 Emergence of the Tea Party

The Tea Party rejuvenated the connection between spending and taxes in response to President Barack Obama’s stimulus bill. The American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009 (ARRA) injected $787 billion into the United States economy via direct federal spending and indirect transfers to states and localities, re/authorizing a range of programs including the Neighborhood Stabilization Program. Until then, debate about the national debt had fallen slack as the War on Terror justified huge amounts of spending to Republicans (and Democrats, at first), while Democrats since the New Deal have accommodated larger deficits in return for social insurance programs. With a Democrat in the White House, anti-tax organizers pointed to the increase in welfare spending as an unconsented-to burden on the American taxpayer and steps down the road toward federal bankruptcy. This movement came to knock on the doors of troubled American homeowners when Rick Santelli, a reporter for CNBC, launched into an tirade from the trading floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange at the thought of the American taxpayer “subsidizing the losers’ mortgages,” calling for a “Chicago Tea Party in July.”105 “CNBC’s Rick Santelli’s Chicago Tea Party” (CNBC, February 2009).

The rant transfigured debt relief into a taxation issue, bundling it with ARRA’s other increases, and making debt relief suddenly legible to the Republican party. In the following days, prominent conservative and anti-tax organizations, such as the Heritage Foundation and Americans for Tax Relief, convened conference calls to capitalize on the opportunity. Rallies around the country and demonstrations by smaller groups of organizers were backed by anti-tax organizations and wealthy conservatives such as the Koch brothers. While this movement garnered criticism that the facially grassroots activity was mere “astroturfing”, it may have nonetheless propelled Republicans to win back the House of Representatives in the 2010 midterm elections. The Tea Party, then both formal Congressional caucus and loose alliance of conservatives, sharpened the connection between government spending and taxation that had been dulled by Bush’s first term. Their politics of debt relief substituted the national debt for household debt, and transfigured the latter into an opponent of anti-tax sentiment.

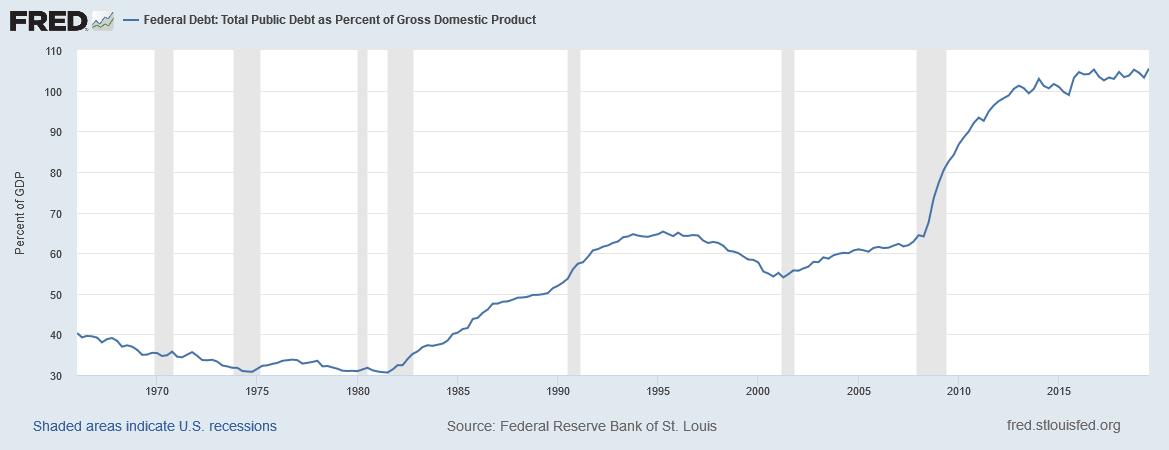

Figure 2.6 shows the total federal public debt as a percentage of GDP. With the exception of Bill Clinton’s second term from 1997 to 2001, it grew at various rates since the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981. And until Obama’s stimulus bill, debt politics entered the national conversation exclusively as the national debt. The debate about the debt shaped the presidential race most dramatically: a nationally-televised town hall debate between Clinton, George H. W. Bush, and Ross Perot in 1992. An ill-informed question about the effects of the national debt on the candidates’ lives is cited by campaign advisers and political analysts as an inflection point in the race when Clinton could connect and Bush could not.106 “Clinton: The Comeback Kid,” Documentary, July 2017. This example serves only to highlight the importance of the question in 1992, and more broadly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when concerns about America’s economic power were heightened by the growth of Japanese and Chinese foreign direct investment. The volume of rhetoric surrounding the debt was perhaps a reason that bipartisan spending cuts were able to pass both houses of Congress.

Figure 2.6: Federal public debt as a percentage of gross domestic product.

Outside the Clinton presidency, however, debt became the norm. Despite George H. W. Bush’s promise of “No new taxes,” Democrats pushed through the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, which raised taxes and introduced restrictions on expenditures in an effort to combat deficit spending, but was unsuccessful in slowing the growth of debt relative to gross domestic product. A generation later, George W. Bush would trigger a very moderate rise in debt-to-GDP, but a very large rise in real (2017) dollars, by increasing military spending from $433 billion in 2001 to $707 billion in 2008107 “Military Expenditure by Country, in Constant (2017) US$ M., 1988-2018” (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2019). and slashing taxes. Finally, the combination of Bush-era bailouts and Obama-era measures to combat the Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession account for the shark fin–looking feature towards the end of the 2000s.

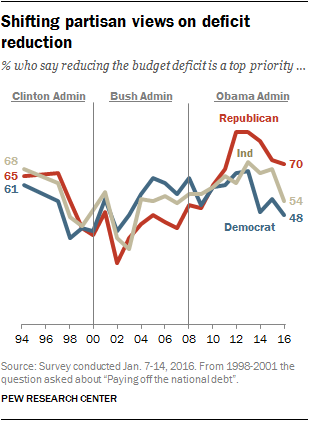

While public opinion polling tracks the spikes and dips of this graph reasonably well, it is confounded by the War on Terror, an expenditure (initially) justifiable by members on both sides of the aisle. In 2002, their first poll since the attacks of September 11, 2001, Pew Research Center tracked a plunge in the percentage of respondents who say that “reducing the budget deficit is a top priority.”108 “Budget Deficit Slips as Public Priority” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, January 2016). Figure 2.7 shows this trend by political party affiliation. Republican-affiliated respondents in 2002, who by the turn of the millennium differ little in number from Democrats and Independents, distance themselves from both affiliations, registering the smallest number of respondents who prioritize the budget deficit between 1994 and 2016. Priorities of the two parties reconvene in 2009, when the economic woes of Bush are inherited by Obama (Pew conducted the poll in mid-January), but diverge once again in 2011, as the new Congress is sworn in following 2010’s midterm elections.

Figure 2.7: Percentage of respondents who say that reducing the budget deifict is a top priority by party affiliation.

Figure 2.7: Percentage of respondents who say that reducing the budget deifict is a top priority by party affiliation.

While increasing Republican rhetoric about balanced budgets and taxation has correlated nicely with Democratic presidencies (and the reverse for Democratic rhetoric) since at least the Nixon administration,109 Campbell, “What Americans Think of Taxes.” the massive expenditure demanded of the government (see Chapter 1) compounded the Republican case that Obama-era spending constitute profligate spending. For Republican critics, the target of choice against Democratic presidents is simple: visible welfare spending. Where Clinton neutralized this criticism by signing into law welfare reform, Obama touted programs during the Recession. Organizations like the Heritage Foundation latched on to this narrative in a 2010 report entitled “Confronting the Unsustainable Growth of Welfare Entitlements”:

According to Obama’s published budget plans, means-tested welfare spending over the next decade will total $10.3 trillion, not including spending for Obamacare. Most of this welfare spendathon will be financed by borrowing from future generations. Not surprisingly, the federal debt will grow to equal nearly the entire national economy by the end of the decade. ¶ This endless spending growth is unsustainable and will drive the nation into bankruptcy.110 Katharine Bradley and Robert Rector, “Confronting the Unsustainable Growth of Welfare Entitlements: Principles of Reform and the Next Steps” (Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation, June 2010).

This passage, like the report as a whole, argues that “means-tested welfare”111 ‘Means-tested’ describes a provision of a public good and/or subsidy that requires of its recipients certain behavior (such as a work requirement) or a certain status, namely that wealth or income be below a particular level. It does not, despite first impressions, provide benefits only to people of means, as do invisible welfare programs such as the mortgage interest deduction. would be responsible for the impoverishment of the US. It draws a connection between the ‘welfare spendathon’ and national debt, though it does not explicitly say—nor give evidence for the argument—that means-tested welfare will cause the American economy to equal the US gross domestic product. I assert that this frame of argument is common among anti-tax advocates, the placement of blame solely on welfare spending for the sin of unbalanced budgets and high taxes (connected elsewhere in the report).

The Heritage Foundation report is a thorough, well-paced, academic echo of the Santelli rant televised to the nation on February 19, 2009. Santelli’s speech recasts the foreclosures of millions—and the mortgage debt of millions more—as a burden on taxpayers, indistinct from unemployment insurance, Medicare, and food stamps. Standing on the trading floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Santelli opens with the claim that “The government is promoting bad behavior!” seeing crises as openings through which moral hazard creeps. In his eyes, the goal of American economic and social policy is to promote personal responsibility and combat theories of change used by countries like Cuba, where they “moved from the individual to the collective.” The foreclosure crisis is not about “subsidize[ing] the losers’ mortgages,” but using market forces to weed out those who make irresponsible or unprofitable investments “and give ’em (the foreclosed houses) to people that might have a chance to actually prosper down the road and reward people that could carry the water instead of drink the water.” Santelli latches on to personal responsibility and strong property rights against a “want to pay for your neighbor’s mortgage that has an extra bathroom and can’t pay their bills.”112 “CNBC’s Rick Santelli’s Chicago Tea Party.” His speech leverages Republican enemies (Communist-controlled Cuba, irresponsible debtors, economic inefficiencies) and friends (the individual, the entrepreneur, personal wealth) to slot this unfamiliar mortgage default problem into a more familiar narrative about personal responsibility and taxpayer burdens.

This moment coincided with burgeoning anti-tax organizations around the country. Americans for Prosperity, founded and backed by brothers David and Charles Koch, had advocated around the idea of a formal, political Tea Party since 2002.113 Eric Zuesse, “Final Proof the Tea Party Was Founded as A Bogus AstroTurf Movement,” HuffPost (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/final-proof-the-tea-party_b_4136722, October 2013). The organization built out chapters around the country, with state chapters growing in power and turning membership rolls into legislative victories.114 Theda Skocpol, Alexandra Hertel-Fernandez, and Caroline Tervo, “How the Koch Brothers Built the Most Powerful Rightwing Group You’ve Never Heard of,” The Guardian, September 2018. After the Santelli affair, rallies of up to a few thousand protesters gathered in cities around the United States, and in September 2009, tens of thousands marched on Washington. The movement had outsize influence due to its insurgency, receiving a jolt of energy when Dave Brat unseated House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, a first in American primary politics.115 Eric Linton, “House Majority Leader Eric Cantor Defeated by Tea Party Challenger David Brat in Virginia GOP Primary,” International Business Times (https://www.ibtimes.com/house-majority-leader-eric-cantor-defeated-tea-party-challenger-david-brat-virginia-gop-1597736, June 2014).

2.3 Conclusion

In sum, the Neighborhood Stabilization Program, by insulating homeowners from the wiles of the market, sought to construct an artificial environment where ownership would bring success. By this aim, the NSP fit in President George W. Bush’s ownership society doctrine, and the asset-backed political economy that had propelled presidential campaigns since Ronald Reagan’s second term as well as the American economy more generally. However, this asset-backed political economy had not received the explicit blessing of the Republican party (or the Democratic party for that matter). At the subnational level, the party focused far more on taxation than on homes; these priorities were complementary (or at least independent of each other) so long as asset prices rose. When these prices fell, and an economy that had reconfigured itself to feed off rising asset prices sputtered, the governmental outlays required to remedy the situation totaled several hundred billion dollars. This price tag met simmering rhetoric about balanced budgets and decreased welfare spending, neither of which came to pass under the economic crisis policies of Bush’s later and Obama’s early years. Preheated by wealthy conservatives, anti-tax organizers heeded the call of Rick Santelli to advocate for lower taxes coupled with lower spending, all wrapped up in the Tea Party movement.

In addition to buttressing my methodology, this chapter described the anti-tax politics that changed a nation of pliant post-War taxpayers116 Campbell, “How Americans Think About Taxes,” 160. into one of activists. Responses to California’s Proposition 13 and reverberations of Reaganite rhetoric led Republicans “to define themselves and their party in opposition to taxes.”117 Martin, “Welcome to the Tax Cutting Party,” 128. Politicians of all stripes followed, with Third Way Democrats, led by President Bill Clinton, accepting tax cuts in their successful political bids; it was only in the 2000s that Democrats united (more or less) in warning against lower taxation.

The mortgage crisis hit after this crystallization of interests: a moment in American politics when the two parties agreed on the content of their debates. Specifically, they agreed that—along with wars in the Middle East—taxation and visible, means-tested welfare were the political issues of the day. The only difference were the moral valences each party attached to the issues.

This connection between taxation, welfare, and party platforms came to a head in the late 2000s. After the mortgage crisis ushered in a financial crisis and the Great Recession, economic policy adopted a militant vocabulary and assumed powers fit for a war. In response, grassroots anti-tax movements (thoroughly astroturfed by conservative donors and non-profits) took up equally rhetorical arms, with CNBC reporter Rick Santelli sounding the battle cry of the Tea Party Movement.

The Tea Party Movement sharpened the debate over taxes. What had been salient in the decades before the trauma of the financial and mortgage crises re-emerged as the GOP’s guiding issue. The salience of taxation, and the formalization of candidates as members of the Tea Party Caucus, made the theoretical underpinnings legible to voting analysis. Without the self-professed and much-discussed focus on taxation during the 2010 midterm elections, analyzing voters’ awareness of candidates’ tax positions would be required in order to effectively argue that voting behavior ran with tax policies. The focus on taxation, and the clear connection between expenditures on visible welfare programs and higher taxation, make possible the aggregation of individual tax preferences into party voting. It also made Democratic the NSP. There are therefore ambiguous political forces at work in a voters conception of foreclosure relief policies: on the one hand, they may be emblematic of the larger welfare state bankrupting the economy on unnecessary programs, triggering a backlash by voters; on the other hand, by raising prices, it may have increased the home equity of voters, pushing their views further right.