Political Impacts of Residential Mortgages in Crisis

Corey Runkel

2020-05-01

Chapter 1 Introduction

![]()

![]()

![]()

This thesis takes up two different kinds of questions that converge with the Neighborhood Stabilization Program (NSP) amid the rise of the Tea Party. The first asks, how can the political effects of housing policy and labor risk be measured? The second asks, why was it the case that housing policy was in a position to affect millions of votes? The first attempts to add to the political science and sociology literature around the connections between housing, political preferences, and voting. This line of analysis is motivated by the opportunity presented by the Neighborhood Stabilization Program, 2010 decennial census, and 2010 midterm elections to bridge a gap in the measurement of political behavior. The NSP and census provide unusually granular and timely data, and the midterm elections posed a unique brand of politics to American voters that politicized key features of housing in the United States, making those features legible to voting analysis. The creation of this brand of politics constitutes my second line of analysis, for this brand of politics was neither usual nor inevitable. Rather, it was a product of the political and economic mechanisms that bind welfare, taxation, and housing together. The historical claims are not new; they have been fashioned directly from the work of others. But they reframe my analysis in order to communicate the significance of my claims beyond their contributions to the literature.

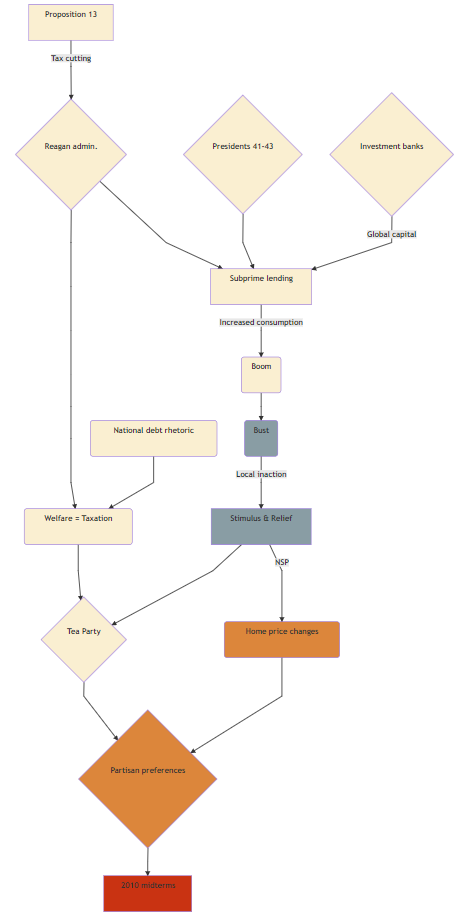

Understanding the relationship between these two lines of analysis is imperative to evaluating my argument about the impact of the Neighborhood Stabilization Program. To that end, I have provided Figure 1.1. A big theme here is the enduring power of anti-tax rhetoric to cast features previously invisible to politics in a political light. For instance, I will argue that this rhetoric politicized particular welfare programs in the 1980s (not very contentious) and then residential foreclosures a generation later (somewhat more contentious). Also evident in this diagram is a bifurcation of rhetoric and policy. This bifurcation bluntly describes a historical process but nicely captures my argument’s flow: on the one hand an anti-tax movement led Reagan to the presidency and grew to color much of the ensuing presidential elections, even as its objects were marginal differences in revenue and small chunks of expenditure; on the other hand, policies that defined American economic growth in the 1990s and early 2000s were left out of the political limelight.

Another theme is that policies and politics can make available for public inspection private preferences. This mechanism operates in the same way demand for an innovative product demonstrates an appetite never before imagined. Here that demand is measured in votes, the product is a well-defined conservative candidate, and the appetite is a home equity–induced penchant for lower taxes and less welfare. Measuring the effects of a crisis on political behavior is not predicated on the presence of such well-defined conservatism in the Tea Party, nor on the public boundaries of the Neighborhood Stabilization Program. Rather, their coincidence allowed for differences among the electorate to map on to choices at the ballot box.

Figure 1.1: Diagram of the argument, by chapter: gray = ; tan = ; orange = ; red = .

1.1 An Unfurling Crisis

Between 2007 and 2012, 10 million Americans—1 of every 20 adults—lost their homes.1 Isaac William Martin and Christopher Niedt, Foreclosed America (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2015), 5. Mortgages originated in 2006 and 2007 respectively suffered default rates double and quadruple the rates of those originated in 2004,2 Herman M. Schwartz and Leonard Seabrooke, eds., The Politics of Housing Booms and Busts, International Political Economy Series (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2009), 200, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230280441. with many of them clustering in the Sand States of California, Nevada, Arizona, and Florida. Countrywide Financial, which two years earlier had serviced 20% of US mortgages,3 Schwartz and Seabrooke, The Politics of Housing Booms and Busts. collapsed in July 2008 (though it was subsequently resurrected under Bank of America). By 2009, median net worth had plunged 45%.4 Matt Stoller, “The Housing Crash and the End of American Citizenship,” Fordham Urban Law Journal 39, no. 4 (February 2016): 1214.. This in a country where the housing stock accounts for fully 9% of global wealth.5 J. Adam Tooze, Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World (New York: Viking, 2018), 43. Despite the scale of vested interests, neither homeowners, banks, nor local governments wielded much power in the response to the subprime mortgage crisis.

Instead, Congress passed the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA). It authorized the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to distribute $3.9 billion to state and local governments for the purchase and repair of foreclosed properties.6 Nancy Pelosi, “Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008,” July 2008. This program, later termed the Neighborhood Stabilization Program, purchased, repaired, and resold vacant properties in order to mitigate the effects of foreclosures on their surroundings. Primarily, foreclosures tear people from their homes. On top of this comes the stigma of being a “deadbeat”7 David Dayen, Chain of Title: How Three Ordinary Americans Uncovered Wall Street’s Great Foreclosure Fraud (New York: The New Press, 2016). debtor and mounds of fees—legal, cancellation, transportation-related. But once homeowners have been forced out, the neighborhood and municipality bear the financial weight of that foreclosure.

To nearby homeowners, foreclosures cost on average $159,000 in decreased property values.8 Daniel Immergluck, Foreclosed: High-Risk Lending, Deregulation, and the Undermining of America’s Mortgage Market (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011), 151. To the city or county that envelops the property, it costs around $50,000 for the legal and construction work to demolish and resell a vacant lot, parcels which tend to drop property values even further.9 Daniel Indiviglio, “The Housing Stabilization Program You Haven’t Heard About,” The Atlantic (https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2010/04/the-housing-stabilization-program-you-havent-heard-about/38739/, April 2010). When property values drop, a home’s [apparent] equity drops too. Home prices, estimated constantly by firms such as Zillow and appraised periodically by taxing authorities, determines to a large extent the wealth and borrowing power of homeowners. If the value of an already-mortgaged home rises, homeowners can refinance. While refinancing most often takes advantage of lower interest rates or decreased principal amounts to reduce monthly payments, refinancing was used instead to finance renovations, service debts (eg. student, credit card, and car loans), or cash out. Lenders willingly converted apparent value into real value, and as long as home values crept up, refinancing was viable. This use of refinancing reflected a shift in how Americans approached housing, from the home solely as a socially private good, to the home also as an asset. In this way, homes stand increasingly in the position of pension plans and 401ks: a wise move can transform forty years into four-hundred thousand dollars.

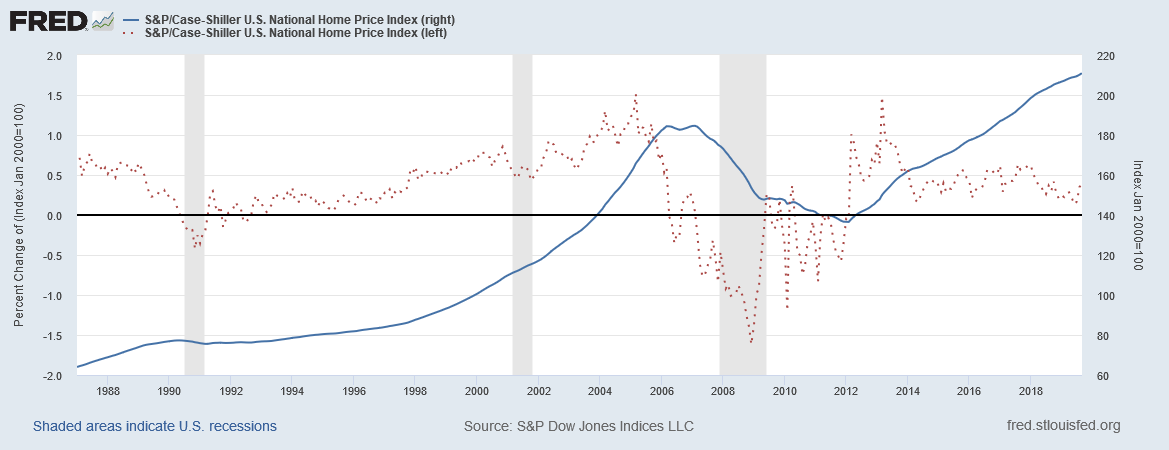

Such wisdom seemed ubiquitous from September 1992 until March 2006. As Figure 1.2 shows, the intervening 14 years never once saw a drop in the industry’s standard home-price metric, the Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index. As prices rose, homeowners refinanced, effectively paying back the first mortgage while taking out the second. To investors in mortgage-backed securities (MBS), pre-payment from refinancing is usually seen as a risk, but constant and predictable refinancing added to the safety of securitization, playing into investors risk-reward calculus. However, when prices fell—or even flatlined—this safety evaporated. Without the increased [apparent] home equity, refinancing served no purpose. Falling prices instead saddled homeowners with their current mortgage, often one whose interest rates reset after two years, climbing an interest-rate staircase for the next 28 years. Where previously refinancing had arrived to dig out homeowners from piles of debt, living expenses (and non-mortgage debt) continued to accumulate.

Figure 1.2: Price (right axis) and growth (left axis) of the Case-Shiller Home Price Index, adjusted for seasonal price fluctuations.

These factors make homeowners very sensitive to falling or stagnant home prices. In their sensitivity, they may have voted for parties, candidates, and policies they believed would drive up home prices, like property tax cuts, muscular code enforcement, and spacious zoning regulations. Each of these policies reduces the resources available for non-homeowners, pitting homeowners against renters, the homeless, and anyone else without a direct financial stake in the asset. For example, tax cuts, take they the form of property tax slashes or the home mortgage interest deduction, reduce the monies available to fund public goods, keeping that money in households. “Housing elements of the U.S. welfare state,” Schwartz & Seabrooke note, “favor everyone but the ‘poor.’”10 Schwartz and Seabrooke, The Politics of Housing Booms and Busts, 212. This logic—that higher taxation means money flow from wealthy people to poor people—rationalizes the fear that any rents extracted from higher taxation will not return to homeowners. Circling back to the original home-price dynamic, higher home values fund greater consumption, while lower property values and higher taxes constrict household budgets.

As prices rose, creditor and debtor interests laid at some angle, intersecting in the particular case of safe, two-year refinancing, but divergent in the general [debtor-friendly] case of refinancing to take advantage of lower interest rates. On the other hand, falling housing prices conformed the immediate interests of creditors and debtors to one another, since delinquency and default eliminated any chance of extracting further rents. Fears of a debt spiral triggered by falling home prices also beset cities,11 Mark Muro and Christopher Hoene, “Fiscal Challenges Facing Cities: Implications for Recovery” (Brookings, November 2009). though there is some doubt that those fears were justified.12 Liz Gross et al., “The Local Squeeze: Falling Revenues and Growing Demand for Services Challenge Cities, Counties, and School Districts,” ed. Susan Urahn (Philadelphia: Pew Research Center, 2012); Byron Lutz, Raven Molloy, and Hui Shan, “The Housing Crisis and State and Local Government Tax Revenue: Five Channels,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, Special Issue: The Effect of the Housing Crisis on State and Local Governments, 41, no. 4 (July 2011): 306–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2011.03.009. With these interests in syzygy, why didn’t homeowners, investors, or cities assert solutions, even ones that were done chiefly in their own interest?

1.2 Why federal relief was needed

I argue in this chapter first that homeowners remained quiet due to changes in the foreclosure process from the Great Depression, the differential character of housing versus farming, and narratives about mortgage debtors. Second, the incongruity—spurred by the demise of savings and loans—between incentives for principals in mortgage-backed securities and incentives for the agents tasked with servicing the underlying mortgages, along with fraudulent mortgage transfers, limited the ability of creditors to act. Third, I point to municipal disinvestment and the trajectory of the Commerce Clause as reasons why cities were unable or unwilling to respond to mass foreclosures. This argument serves dual purposes, simultaneously introducing the political-financial-legal interfaces at work in housing politics, and explaining why federal action was necessary in the first place.

1.2.1 Homeowners were Unable to Organize

The powerlessness of anti-foreclosure organizing can be explained by comparison with the most powerful anti-foreclosure campaigns of the Great Depression. I compare the two on their positions within the greater economy: where the food system of the 1930s allowed for relatively immediate connections between Midwestern farmers and the nation’s supermarket shelves,13 Michael Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma (Place of publication not identified: Penguin Group US, 2006). the American welfare and credit system exaggerated the multiplier effects of housing in American economic growth.14 Schwartz and Seabrooke, The Politics of Housing Booms and Busts, 27. Legislative movements require a base of public opinion and support, a mouthpiece through which opinion can be articulated, and a powerful audience to hear those articulated opinions and demands. Foreclosed housing’s base of public opinion and support was attenuated by the geographic diffusion of subprime mortgages which limited fora for communication, both internally and externally. In addition, the organizers’ audience (legislators) was crowded out by other demands, including the political presence of mortgage servicers. The Great Depression, however, saw these factors come together in the Midwest, where farms were physically parched and thus, financially underwater.

Farmers were positioned similar to homeowners who adopted cash-out refinancing in that they relied on their land for its income. However, farmers in the Great Depression differed from early 2000s subprime borrowers in that farming did not supplement wage incomes, it replaced wage incomes. In addition, access to government and stark differences in media portrayal combined with the larger impact of farm foreclosures to drive organizing that led to 27 states enacting per se or de facto moratoria on foreclosures.15 David C Wheelock, “Changing the Rules: State Mortgage Foreclosure Moratoria During the Great Depression,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 90, no. 6 (November 2008): 537. In contrast, the lack of such conditions pitched the struggle for foreclosure legislation in the subprime mortgage crisis at a severe uphill angle.

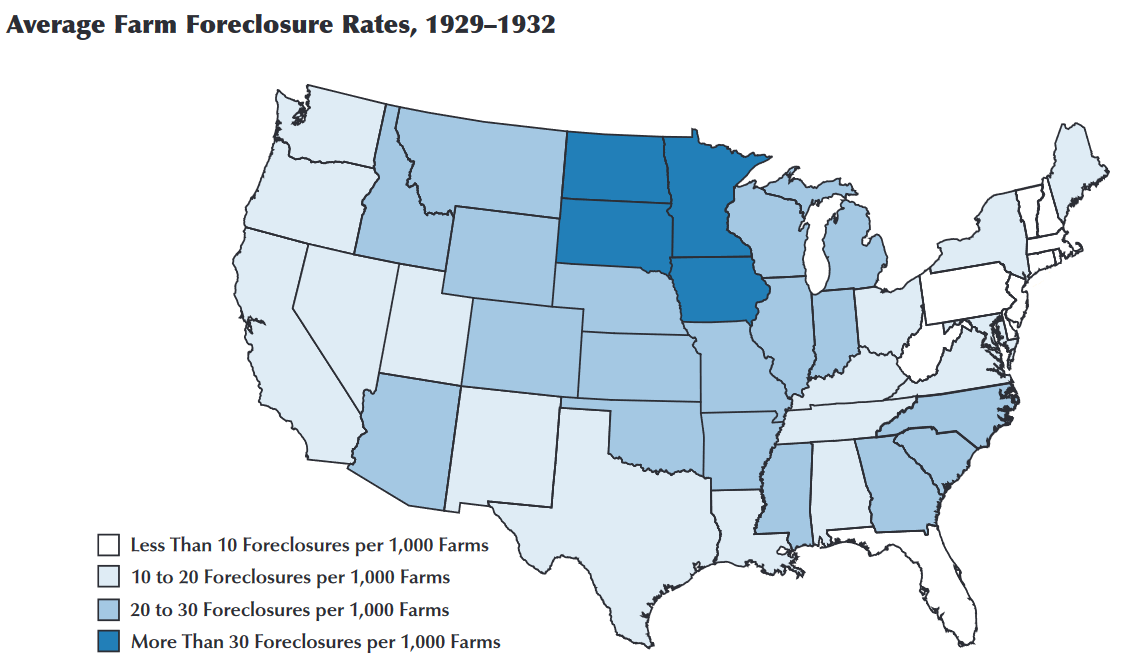

The most important differences between the foreclosure crisis in the Great Depression and that which preceded the Great Recession were the complementarities between farming with organizing. Farms were both the workplace and home of farmers. Unlike the foreclosure crisis in the 2000s, losing a home implied also losing a job. This raised the stakes for farmers to plead for relief and enlarged the macroeconomic worries with which politicians were just beginning to grapple. Of the 100,000 farmers who lost their farms each year between 1926 and 1940,16 Lee J. Alston, “Farm Foreclosures in the United States During the Interwar Period,” The Journal of Economic History 43, no. 4 (1983): 885–903. the Midwest saw the highest concentrations. Figure 1.3 shows the high concentration in Minnesota, Iowa, and the Dakotas, and the lesser concentration all around the Midwest. In 1933, by far the worst year for farm mortgages, failure rates topped 3.7%; during the rest of 1926-1940, rates were often above 1.5%.17 Wheelock, “Changing the Rules,” 571. By contrast, U.S. residential foreclosures reached 2.23% in 2010, the worst year of the foreclosure crisis.18 “U.S. Foreclosure Activity Drops to 13-Year Low in 2018,” ATTOM Data Solutions (https://www.attomdata.com/news/most-recent/2018-year-end-foreclosure-market-report/, January 2019). In part, this is a denominator effect: the 50% down payments and double-digit interest rates caused fewer mortgages to be demanded in the Great Depression. In large part, however, the differences between farms and homes accounted for the scale.

Figure 1.3: Spatial clustering of farm foreclosures. From Wheelock (2008).

Figure 1.3: Spatial clustering of farm foreclosures. From Wheelock (2008).

The geography of farmland created several features that made easier mass organizing. Lower population densities meant that fewer people exercised political power over a fixed-size jurisdiction when compared to a densely-populated district. While this feature could not have played into U.S. Congressional politics, which are apportioned by population, it could make collusion easier in counties. Organization at the county level was important in the Great Depression, because foreclosed properties were sold by sheriffs, elected county officials.19 John A. Fliter and Derek S. Hoff, Fighting Foreclosure: The Blaisdell Case, the Contract Clause, and the Great Depression, Landmark Law Cases & American Society (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2012). Compounding the ease of collusion was the congruency of interests. While farms produce a variety of crops, soil and climate particularities combine with federal agriculture policy to homogenize production locally.20 Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma. In other words, Tobler’s first law of geography holds: “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.”21 W. R. Tobler, “A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region,” Economic Geography 46 (1970): 236, https://doi.org/10.2307/143141. In conversation with the realities of the foreclosure crisis in the 2000s, two conclusions—one ecological, the other sociological—emerge.

On the side of ecology, crop failures occurred in conjunction with nearby farms. The same climate or disease that killed a neighbor’s crops did not stop at the property line. Farmers in the Great Depression shared this feature with homeowners in the mortgage crisis: lowered property values on one side would spillover to the other side. For both populations, spatial correlations were imperfect, as some farmers planted different crops and some foreclosures occurred among conservative borrowers or wholly-owned homes, but the spillover effect mattered.22 Anthony DeFusco et al., “The Role of Price Spillovers in the American Housing Boom,” Journal of Urban Economics 108 (November 2018): 72–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.10.001. Falling property values decreased the value of neighboring properties, deepening the mortgage crisis for farmers in the Depression and homeowners before the Recession. The conditions of localized, severe economic distress existed in both eras.

But this comparison did not subsist between the sociological features of farming and housing. Farming the same crops entails some degree of visiting the same market, buying the same tools, and asking the same people for advice. Farmers met their neighbors whether they liked them or not, creating a forum to talk shop with those nearby. The simple fact of homeownership, however, signifies income, but often little else. Meanwhile, the larger populations of suburbs meant more social and cultural institutions among which residents could choose. The higher density and absolute size of the suburbs separated struggling homeowners from each other, while the lack of farming meant that—even if they had bumped shoulders—their mortgage finances were less likely to be topics of discussion (who talks with their neighbor about mortgage troubles?). While the suburban quality of foreclosures in the recent mortgage crisis could have drawn homeowners closer together through their homeowner association (HOA), HOAs were insignificant bulwarks against nearby foreclosures.23 Ron Cheung, Chris Cunningham, and Rachel Meltzer, “Do Homeowners Associations Mitigate or Aggravate Negative Spillovers from Neighboring Homeowner Distress?” Journal of Housing Economics, Housing Policy in the United States, 24 (June 2014): 87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2013.11.007. As an indication of how weak HOAs were, homeowner association fees were some of the first payments to stop once mortgage debt piled up.24 Casey Perkins, “Privatopia in Distress: The Impact of the Foreclosure Crisis on Homeowners’ Associations,” Nevada Law Journal 10, no. 2 (January 2010): 561. These divergent implications for farming and suburban housing could be added to Robert Putnam’s argument of a secular (in both the economic and religious senses) decline in social capital25 Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2001). to argue that the sociological character of suburbs blocked organization around increasing mortgage delinquency and household foreclosures.

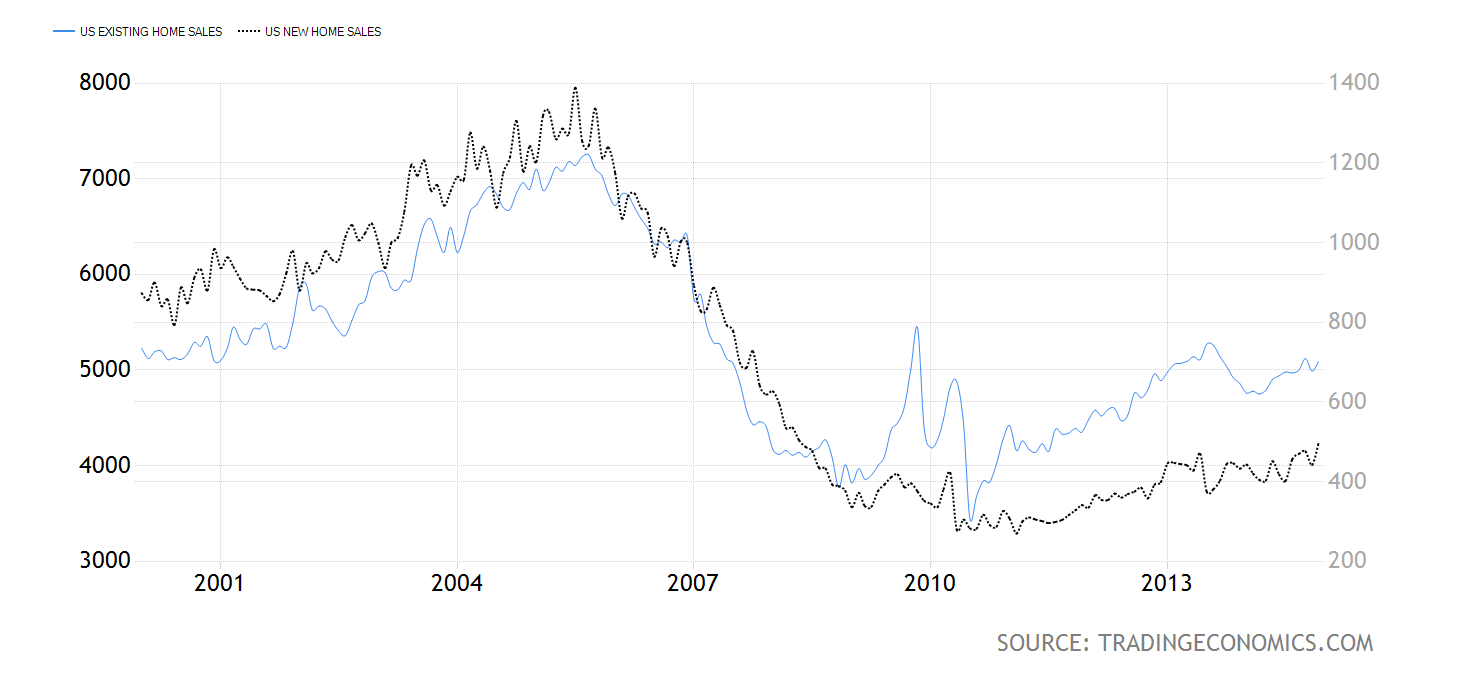

As I mentioned above, the lack of local fora was important. In the Great Depression, not only were county sheriff offices the location of foreclosure sales, they were also the location of foreclosure sale stoppages. Midwest farmers tried boycotting markets and sabotaging crops in transport to grab attention and force up prices, but they “did not seriously threaten urban food supplies or raise prices or the cost of production.”26 Fliter and Hoff, Fighting Foreclosure, 4. Rather, farmers succeeded through intimidation tactics. The “ropes under [farmers’] coats […] stopped thousands more foreclosures than did” self-organized arbitration, according to the then-president of the Farmers’ Holiday Association, Milo Reno.27 Fliter and Hoff, 65. There were more than 100 recorded instances of farmers, sometimes numbering in the thousands, packing county sheriff offices to discourage any would-be buyers, allowing the borrower to re-purchase their farm in full for sometimes as little as a penny.28 Fliter and Hoff, 63. Direct action of this nature was nowhere in the subprime mortgage crisis. Rather than showing a spike in sympathy, Figure 1.4 shows the spike in existing home sales after several million foreclosures had been filed.

Figure 1.4: Existing Home Sales versus New Home Sales, 2000-2014.

Figure 1.4: Existing Home Sales versus New Home Sales, 2000-2014.

But organizing need not have adopted the character of halting foreclosure sales; rather, the foreclosure itself could have been the point of action. Changes to bankruptcy laws made foreclosures less defensible by making judicial hearings an opt-in rather than mandatory system. The hearings provide both the legal forum to contest evidence, claims, and standing, as well as the social forum to support other defendants.29 Dayen, Chain of Title. Courts’ docket sizes also elongated the period a delinquent borrower could stay in their home, during which alternative remedies may be sought.30 Cheung, Cunningham, and Meltzer, “Do Homeowners Associations Mitigate or Aggravate Negative Spillovers from Neighboring Homeowner Distress?” J. Michael Collins, Ken Lam, and Christopher E. Herbert31 “State Mortgage Foreclosure Policies and Lender Interventions: Impacts on Borrower Behavior in Default,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 30, no. 2 (2011): 216–32, https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20559. found that even such vanilla advocacy as mailings suggesting loan modification were more effective in states with judicial foreclosures. However, evidence regarding the change of this process over time is a mixed bag. Cheung, Cunningham, and Meltzer32 “Do Homeowners Associations Mitigate or Aggravate Negative Spillovers from Neighboring Homeowner Distress?” argue that the rights of residents have eroded as the number of states with non-judicial foreclosures are the norm has increased.33 Though the actual number of states where non-judicial foreclosure is legally available has decreased, per Andra Ghent, “The Historical Origins of America’s Mortgage Laws,” Special Report (Research Institute for Housing America, October 2012), 22-23.

Judicial foreclosure briefly entered the national news cycle in 2010, when former homeowners alleged fraud against several large mortgage servicers. Allied state attorneys general settled with 13 banks over their roles in using falsified titles, signatures, and documents to foreclose on 3.8 million borrowers.34 Ronald D. Orol, “U.S. Breaks down $9.3 Bln Robo-Signing Settlement,” MarketWatch (https://www.marketwatch.com/story/us-breaks-down-93-bln-robo-signing-settlement-2013-02-28, February 2013). Fraudulent documents meant that judicial foreclosures, normally very cut-and-dry affairs, were suddenly contentious. In fact, the New Jersey Supreme Court in 2010 ordered lower courts to stop hearing foreclosure cases due to the prevalence of fraudulent documents.35 “New Jersey Courts Take Steps to Ensure Integrity of Residential Mortgage Foreclosure Process” (New Jersey Courts, December 2010). Organizers cited the political influence of these so-called foreclosure mills—particularly in hard-hit Florida, the only Sand State with mandatory judicial foreclosure—as cause for the inefficacy of activism around foreclosure fraud. In several cases, the Florida Attorney General and elected representatives backed out of supporting investigations after meeting with employees of mortgage servicers (who were, in two cases, also employees of the Attorney General),36 Dayen, Chain of Title. while several politicians including Senate Banking Committee Chairman Christopher Dodd were embroiled in a scandal that saw them receive below-market interest rates and reductions on mortgage payments.37 Glenn R. Simpson and James R. Hagerty, “Countrywide Friends Got Good Loans,” Wall Street Journal, June 2008. Whatever the cause, the fraudulent mortgage documents offered a concrete opportunity for organizing that resulted in the dislocation of millions, and undermined a tradition of impeccably-kept land records that extended well before 1776.

Geographic and economic features of farming compounded its larger-scale mortgage crisis to foment conditions ripe for organizing. Farming’s power to determine social interactions pushed together those in distress. By contrast, the Internet forums where foreclosures were discussed and debated turned out to be silos, with arguments accumulating inside but little action leaking out. As farmers often find themselves in financial distress, they built on top of established organizing networks, joining a long line of Progressive debtor’s rights movements in the Midwest. In contrast, homeowners had been trained to prefer low inflation rates: here access was more important that the burden of debt. The organized farmers articulated political demands most remarkably on March 22, 1933, when “a caravan of two to three thousand farmers descended upon St. Paul from southern Minnesota, in an astonishing array of antediluvian automobiles, and swarmed over the capitol.”38 Fliter and Hoff, Fighting Foreclosure. This swarm presaged the unanimous passage of the Minnesota Moratorium Act, a key piece of state mortgage legislation whose constitutionality would be upheld in Home Building & Loan Association v. Blaisdell,39 “Home Building & Loan Assn. V. Blaisdell,” January 1934. paving the way for further states to enact statutory protections for mortgagors during the Great Depression. But during the mortgage crisis, calls for mortgage moratoria were met with consternation, as scholarly opinion soured on Blaisdell. To see why state resources went unspent, I look again to the legal history of economic regulation in the United States, and tour briefly the trend of municipal disinvestment.

1.2.2 City & State Administrations Could Not Handle Foreclosures

The Commerce Clause was written, and did develop, with the express purpose of pre-empting states’ right to economic legislation. Indeed, its development in legal precedent followed such a pattern in the 1800s and 1900s, upholding regulation based on the Commerce Clause as constitutional whenever business touched multiple states. This criterion is important to foreclosure policy because of the spillover effect of foreclosures. Such effects respect no legal boundary and found themselves under federal jurisdiction by way of the Commerce Clause. Later in the twentieth century, tax reform organizations yanked the reins of state and municipal budgets. This influence combined with federal urban policy, altering expectations about the level of regulation cities should undertake, and leaving only growth-oriented tax incentives and zoning protocol in the regulatory toolbox of cities and states This turn away from local economic regulation starved states and cities of the resources needed to handle foreclosures.

Features of the U.S. Constitution were interpreted by the Supreme Court to justify federal action, which is partially responsible for the shift in spending from states and municipalities to the federal government (see Figure 1.5). While scholarship has elaborated (and debated) Charles Beard’s story of private interests in the Constitutional Convention, An Economic Interpretation of the U.S. Constitution is still valuable for its analysis of primary sources. In it, Beard argues that the United States has a long history of enforcing the rights of creditors over the sovereignty of states. Linking uprisings such as Shays Rebellion to foreign credit demands and the interests of individual urban bondholders, he suggests that the Constitution can be seen broadly as a struggle between farmers and bondholders, not unlike Depression-era rhetoric between Midwest farmers leaden with debts and their Eastern creditors.

The primary result of this struggle was the Contract Clause:

No State shall […] coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts40 James Madison, “The Constitution of the United States,” June 1788.

The Contract Clause limited state powers for economic regulation in three main ways. First, it removed from states the ability to print money, and, thus, to overprint money. While a central bank had not been created yet, the Contract Clause ensured that no state could chip away at debt by inflating its currency. Two, the Clause made standard payment in metal, limiting states’ purchasing power (there is only so much metal to go around). Third, this bit of the Constitution, in its statements regarding “ex post facto Law” and “impairing the Obligation of Contracts”, removed from states the ability to cancel debts by removing the ability to cancel private contracts. Debt cancellation or reduction was a primary aim of uprisings like Shays Rebellion and, more softly, wealthy planter political connections.41 Charles A. Beard, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1913).

In the Great Depression, the meaning of the Contract Clause was challenged, as mentioned, in Blaisdell. But scholarly opinion had soured on Chief Justice Charles Hughes’ words that, “While emergency does not create power, emergency may furnish the occasion for the exercise of power.” Richard Epstein, one of the Chicago School’s leading legal scholars, wrote that “the police power exception has come to eviscerate the contracts clause,”42 Richard Epstein, “Toward a Revitalization of the Contract Clause,” University of Chicago Law Review 51, no. 3 (June 1984): 738. and he is not alone. Indeed, Tim Geithner, Treasury Secretary under President Barack Obama, made sure to emphasize legality as one of the tenets of his crisis responses, and pointed to state usage of the Contract Clause as a grey area.43 Christian McNamara, “Yale Program on Financial Stability Interview,” October 2019. Constitutional limits on state (and thereby local) economic regulation were bolstered by scholarly backlash and the significant influence of originalism and textualism on the Court. If Beard’s interpretation of the Contract Clause’s intent was correct, then conservative justices would likely have blocked any such attempts to establish the foreclosure moratoria imposed during the Depression.

The recent turn back towards honoring such intents has limited states from pursuing such monumental measures as moratoria. But within the scheme of regulating business dealings, the Clause left states with great room to move. This range of movement was restricted further by the twentieth century interpretation of the Commerce Clause. While both the Contract and Commerce Clauses reflected Hamiltonian designs on state sovereignty, they have been invoked differentially by Republicans and Democrats, situating themselves on an axis with pro- and anti-business ends. Defenders of the Contract Clause’s intended usage prioritize the right to contract as pre-political, with priority over the rights of local government. Defenders of the Commerce Clause prioritize the federal government’s capacity and judgment to regulate business that stretches across state lines over the right of local government. Unlike the Contract Clause, whose recent judgments and scholarship point to unconstitutionality of state-passed foreclosure moratoria,44 Note that the New Jersey “moratorium” was neither a legislative act nor a blanket moratorium. It affected the litigation of foreclosures and referenced the validity of evidence itself, which would hypothetically be inadmissable regardless of the order. the Commerce Clause has been granted broad powers, with conservatives on the Court only tinkering at the edges of its range of freedom.

For instance, while Blaisdell squeaked by with a 5-4 decision, Wickard v. Filburn unanimously upheld the authority of the Agricultural Adjustment Act to regulate private acts—ones that had never seen a marketplace—which substantially effected the business of another state.45 “Wickard V. Filburn,” October 1942. Wickard capped five to seven years of the Supreme Court leveraging the Commerce Clause’s to authorize New Deal policies. If the powers extended down to peoples’ private properties, what jurisdiction did the federal government not possess? For the mortgage crisis, this history of Commerce Clause–facilitated pre-emption meant that the federal government was expected to intervene during economic crises. All that was needed to authorize pre-emption was the substantial effects test employed in Wickard. Let me be clear on this point: pre-emption via the Commerce Clause did not crowd out state investment; in fact, there is ongoing debate as to whether federal dollars increase state investment.46 Cf. “flypaper effect” in public finance scholarship. Rather, the New Deal wielded the Commerce Clause to achieve its own separate ends, which transferred the balance of responsibility from the state to federal level. Over time, the substantial effects test came to mean that even supposedly-private activities could be federally regulated. Home construction, and possibly foreclosure, given their spillover effects, certainly hit this threshold. Effectively, I argue that a coincidence of responsibility, and a history of the federal government taking on responsibility in times of crisis, meant that states presumed the ball was in Washington’s court. This stands in contrast to the Contract Clause, the interpretation of which has limited state options.

Figure 1.5: Government spending and revenue as a percentage of GDP. While secular growth is present at all levels of government, note the spikes during the Great Depression, Recession, and wars.

As federal responsibility grew and local responsibility concomitantly shrunk, homeowners began throttling property taxes, which account for 70% of municipal revenues.47 Herman M. Schwartz, Subprime Nation: American Power, Global Capital, and the Housing Bubble, Cornell Studies in Money (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 181. The tax revolts, beginning with California in 1978, play a crucial part in the ideological formatting of reactions to the subprime mortgage crisis, but for now I will focus on their effects on revenues. Tax revolts, and tax reform movements more generally, have been significant political forces at all levels of American politics. Whether in regards to a specific tax or taxation generally, taxpayer movements focus on limiting or rolling back tax rates and taxable activity. Their efficacy, however, has been limited; in many cases, revenue and spending provisions can be circumvented to meet legislative and administrative desires.48 Gross et al., “The Local Squeeze.” So, while specific taxes have been reined in by voters, the level of taxation is difficult to wrangle.

The exceptions to this rule are measures that require legislative supermajorities or popular referenda to raise rates. For instance, the original California movement succeeded in restraining property tax rates from climbing above 1% and required a legislative supermajority equal to that needed to amend the state constitution in order to raise special taxes. Provisions such as this have been successful at limiting property tax receipts,49 Sharon N. Kioko and Christine R. Martell, “Impact of State-Level Tax and Expenditure Limits (TELs) on Government Revenues and Aid to Local Governments,” Public Finance Review, May 2012, https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142112438460. effects which bear directly on state and local abilities to raise revenue from housing. In housing-rich states—such as California, Florida, Nevada, and Arizona—that saw so much of their housing stock go vacant, this feature puts a double-bind on states and localities. It implements a strongly pro-cyclic revenue structure that conflicts with the anti-cyclic need for government investment,50 John Maynard Keynes and Paul R. Krugman, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). though such a gap would not grow until assessments had revalued property in the face of the housing bust.

In 2007, 2008, and 2009, this feature likely acted as the lower arm of a pair of price scissors to homeowners—though they were very rusty, unable to close completely since property taxes rarely top 2%—holding stable as housing prices plummeted. There is little research of this effect on municipal finances, but more recent scholarship points to large decreases beginning in 2009 or 2010 and extending as late as 2013.51 Howard Chernick, Andrew Reschovsky, and Sandra Newman, “The Effect of the Housing Crisis on the Finances of Central Cities,” in Housing Markets and the Fiscal Health of US Central Cities, 2017, 18; Gross et al., “The Local Squeeze.” The size of this lag may account for the lack of consensus on the topic, with 2011 research by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors denying significant fiscal effects of foreclosures.52 Lutz, Molloy, and Shan, “The Housing Crisis and State and Local Government Tax Revenue.” At any rate, while property taxes did strain municipal budgets, and while cities did not feel the effects until after the foreclosure crisis elicited policy responses, anxiety over the coming problems mounted.53 Brady Dennis, “Falling Home Values Mean Budget Crunches for Cities,” Washington Post, December 2011; Susan Saulny, “Financial Crisis Takes a Toll on Already-Squeezed Cities,” New York Times, June 2008, 16.

I have outlined structural forces that limited the legal and fiscal capacities of states to intervene in private activities, even when such activities have heavily public effects. While the structural forces clearly affect much more than housing, the funding of American states and towns is heavily indebted towards property taxes, bringing one of every three municipal dollars. While property taxes had not yet declined when the foreclosure crisis hit its lows, anxieties were rising, and taxpayer reform movements had already bit large chunks out of the ability to raise money. These forces starved states and cities of the resources necessary to handle foreclosure. Endowed only with powers to issue zoning regulations, tax incentives, and other growth-oriented policies,54 Samuel Stein, Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State, Jacobin Series (London ; Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2019). cities and states were less able to handle the wave of foreclosures that forced one of every twenty American adults out of their home.

1.2.3 Investors were Unable, and Banks Unwilling, to Limit Foreclosures

The separation of investors from mortgage servicers constituted a separation of ownership from control. Following the institutional literature,55 Adolf A. Berle and Gardiner C. Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A: Transaction Publishers, 1991). this separation led to perverse incentives: while investors lost money from foreclosures, the trustees of mortgage-backed securities gained money from foreclosures. Securitization severed the communicative link between investing and mortgage servicing. When their interests were pitted against one another, the legal priority fell to the trustee, in whose interest it was to foreclose. Before the separation of ownership from control in mortgages, a bank could decide—as many did in the Great Depression—not to foreclose in spite of its legal right.

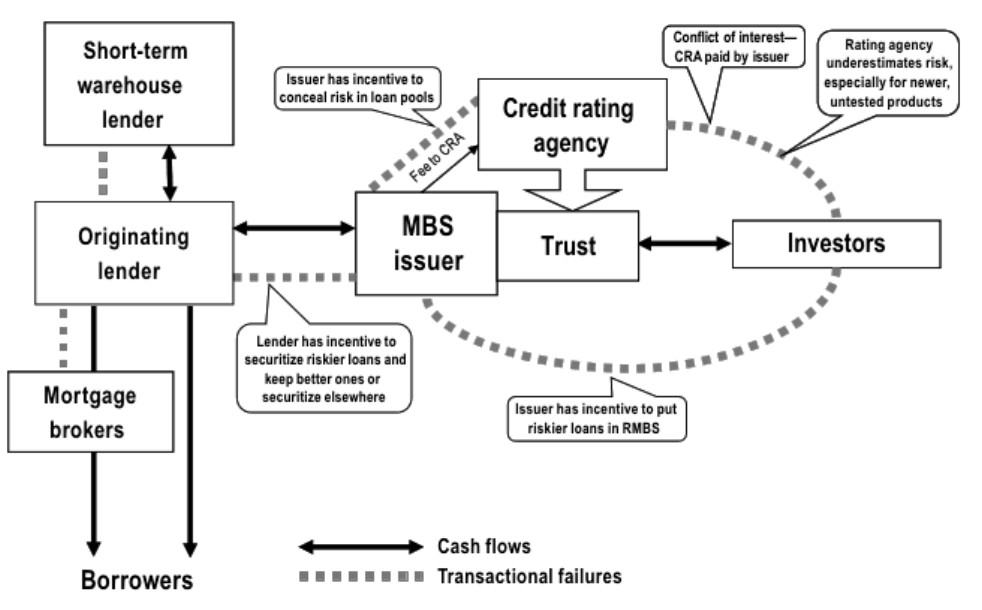

Securitization is a complicated process; Figure 1.6 depicts the flow of legal responsibility from brokerage to mortgage-backed securities (MBS). First, a mortgage broker secures the original agreement between mortgagor and mortgagee. For the homeowner, this is most often all they ever see, and for the broker, this had been most all there was until the 1970s. At that time, the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) were spun off by the federal government into the government-sponsored entities that existed until the mortgage crisis. Fannie and Freddie brokered mortgages to prime borrowers, those considered least likely to default. Yet the stability of individual homeowners could only lower the price of credit (aka interest rates) by so much. Securitization offered a second layer of insulation from the unpredictability of individuals, leading to lower risk, and lower interest rates, making mortgages attractive to prospective homeowners. In this case it was the knowledge that investors would accept low interest rates—made acceptable by global disinflation and a massive supply of savings56 Schwartz, Subprime Nation.—which facilitated such attractive interest rates. After brokering a mortgage, Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac would then take a few thousand other mortgages and combine them into a mortgage pool. Later these pools would contain mortgages brokered by dozens, perhaps hundreds of firms, who would immediately sell them to originators. These two roles, broker and originator, separated over time, and created the initial problems whereby bad loans were good business.57 Immergluck, Foreclosed, 103.

After pooling, the securitizer would then establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV) with the sole purpose of holding mortgages and issuing financial securities. Instead of issuing pieces of individual mortgages, the vehicle issued pieces of itself, a self that was fully composed of the cashflow from mortgages, in the form of claims on the pool’s profits. These profits would then be divided into tranches corresponding to different levels of risk, and thus, reward for the investor. Legally, the tranches specified who would be paid first and who would suffer losses first, with low-risk investors insulated from both heavy gains and heavy losses. I use the word profits deliberately: while the claims were considered “pass-through”, meaning that revenue from mortgages was attached legally to payments to investors, there were costs to securitization. The special purpose vehicle took on the mortgage pool itself, thus obligating it to service the underlying loans. SPVs, with no legal employees, designated companies in their founding documents to act as servicers, scheduling fees for particular services. While investors could open informal lines of communication with those tasked by securitizers to administer payments, there was no formal mechanism by which investors could exercise the kind of shareholder democracy that had become so near and dear to their hearts.

Figure 1.6: Organization of securitized mortgage lending. Taken from Immergluck (2011).

The practical particularities of SPVs severed any remaining lines of communication by which investors could express their interests. While interests would not have been congruent with homeowners, they may have been coincident. During the Great Depression, Prudential, then the largest holder of farm debt in the country, voluntarily ceased collection on farm mortgages.58 Fliter and Hoff, Fighting Foreclosure, 65. Foreclosure ensures that a mortgage debts can never be collected, as it terminates the contract linking debtor with creditor. In normal times, foreclosure (and subsequent sales) may be a good way to hedge against nonpayment, and it was in this framework that servicers were promised payments for enforcing property rights by foreclosure actions. But in a housing crisis, when flattening home values give way to falling, and then plunging home values, adding more supply to a housing market only serves to decrease prices more. Securitization provided agents, the mortgage servicers, to escape the interests of the principals, investors. By removing the principal from the process, MBS securitization granted the agent free[r] reign.

While foreclosures were in the interests of the mortgage-servicing agents,59 Peter S. Goodman, “For Mortgage Servicers, an Incentive Not to Help Homeowners,” The New York Times, July 2009. they were less likely to be in the interests of investors. Depending on their tranche in an MBS, some investors would have actually preferred to keep loan terms stringent in order to increase risk, and thus reward. These inter-investor squabbles meant that servicers that acted along informal lines of request “may be seen as instigating interparty litigation.”60 Immergluck, Foreclosed, 103. I do not argue that investors necessarily would have ceased foreclosure in times of crisis, but that, like banks in the Depression that were long in their own investments, they may have added extra time for payment had they the organizational mechanisms to do so. It is likely that the historical reality of American residential mortgage-backed security would have prevented this anyway: foreign capital held 20% of residential MBS in the United States.61 Schwartz, Subprime Nation. Where thrifts and even large retail banks in the Great Depression had a choice, the clauses in pooling & servicing agreements ensured that the information flow only went in one direction, from mortgage to investor. Securitization, in separating ownership from control of the underlying mortgages, made bad loans good business, as detailed by Michael Lewis’ bestseller The Big Short, but an overlooked aspect of securitization was its alignment of interests after loans had gone bad.

I have identified structural factors that explain why three of the four direct interests in housing—homeowners, cities and states, and investors in residential mortgage-backed securities—were unable or unwilling to organize large foreclosure relief efforts. In the first and third cases, actors were unable to organize due to differences in the political economy (and often, geography) of the subprime mortgage crisis when compared to the Great Depression. In the case of cities and states, federal pre-emption and strained finances limited their legal and fiscal capabilities. These arguments are not exhaustive, but serve to quickly explain why federal intervention in foreclosure relief efforts was necessary.