Chapter 3 Asset Prices, Individual Preferences, and Foreclosures

Keynes took it for granted that current consumption expenditure is a highly dependable and stable function of current income.

How do asset prices affect voter decisions in extremis? Political economists have investigated the impacts of wealth and labor market risk on welfare preferences, but they have yet to investigate how such policy preferences are represented in political decision-making, or how such preferences are changed by movement along the wealth distribution. This analysis seeks to use the Neighborhood Stabilization Program, which aimed to affect neighborhoods in greatest need, to tease out these impacts. Pursuing this question lengthens the focal point from groups to individuals.

This chapter begins by reviewing the political science, sociology, and economic literature on asset-based social insurance preferences, the psychology of lost and gained wealth, and standard models of American voting behavior. It works to develop its own model of voting that will be leveraged in Section 4.3.2 to analyze returns from the 2010 midterm elections, when the Tea Party experienced its first and greatest victories. This chapter stands logically between my last two. It describes how the financial crisis—the characteristics of which were explored in Section 1.1—mutated individual preferences, preferences which then found a home among the political landscape described in Chapter 2.

3.1 The Role of Home Prices

At base, I describe individual consumption preferences from a life-cycle/permanent income perspective. Milton Friedman opened his foundational work in life-cycle analysis by noting that Keynes understood economic fluctuations and crises in terms of the past and present, as gluts or dearths of savings.118 Keynes and Krugman, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. What future tense that did factor into his understanding was almost immediate—the notorious “animal spirits”, for instance, or plunges in the business cycle—rather than the decades-long swings described by Simon Kuznets. Friedman addressed the idea that individuals’ income derives not simply from current income, or previous savings, but from all future earnings. In an extreme example, a toddler able to form “rational” (some fuzziness on this term’s definition) expectations of future income could finance their upbringing and education by borrowing against those predictions, this would be a rational choice for both toddler and financier. This framework sees wealth, and therefore housing, as potentially permanent income.119 Milton Friedman, “Introduction to "A Theory of the Consumption Function",” in A Theory of the Consumption Function, National Bureau of Economic Research General Series 63 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1957), 1–6.

But housing can also be used as a financial “buffer stock” against emergencies. This refinement is motivated by historical facts about American saving habits.120 Christopher D. Carroll, “Buffer-Stock Saving and the Life Cycle/Permanent Income Hypothesis,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112, no. 1 (1997): 1. In 2007, about as many households saved for retirement (33.9%) as for unexpected expenses (32.0%). In addition, only 56% of households saved in 2007, with dramatically lower rates at lower levels of the income distribution.121 Brian K Bucks et al., “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2004 to 2007: Evidence Form the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, February 2009, 9–10. Combined with relatively strict unemployment insurance benefits, these behaviors mean that Americans are by and large exposed to income shocks.

In light of their perceptions regarding risk, how one plans to pay for emergencies feeds into that person’s politics. Understanding the home doubly as an insurance-supplying asset shapes homeowners’ political decisions. This claim is supported by the fact that homeowners are represented worldwide by conservative political parties.122 Ben Ansell, “The Political Economy of Ownership: Housing Markets and the Welfare State,” American Political Science Review 108, no. 02 (May 2014): 387, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000045. Of course, it could simply be the case that high-income people, those who are more likely to own a home, tend to be more conservative. Or, perhaps those who own homes value it as “a refuge from urban corruption,”123 Stern, “The Inviolate Home.” and the idea of leveraging one’s home instrumentally for financial gain is vulgar to such a person’s traditional social values. But these alternative narratives cannot embrace particular features of American household finances.

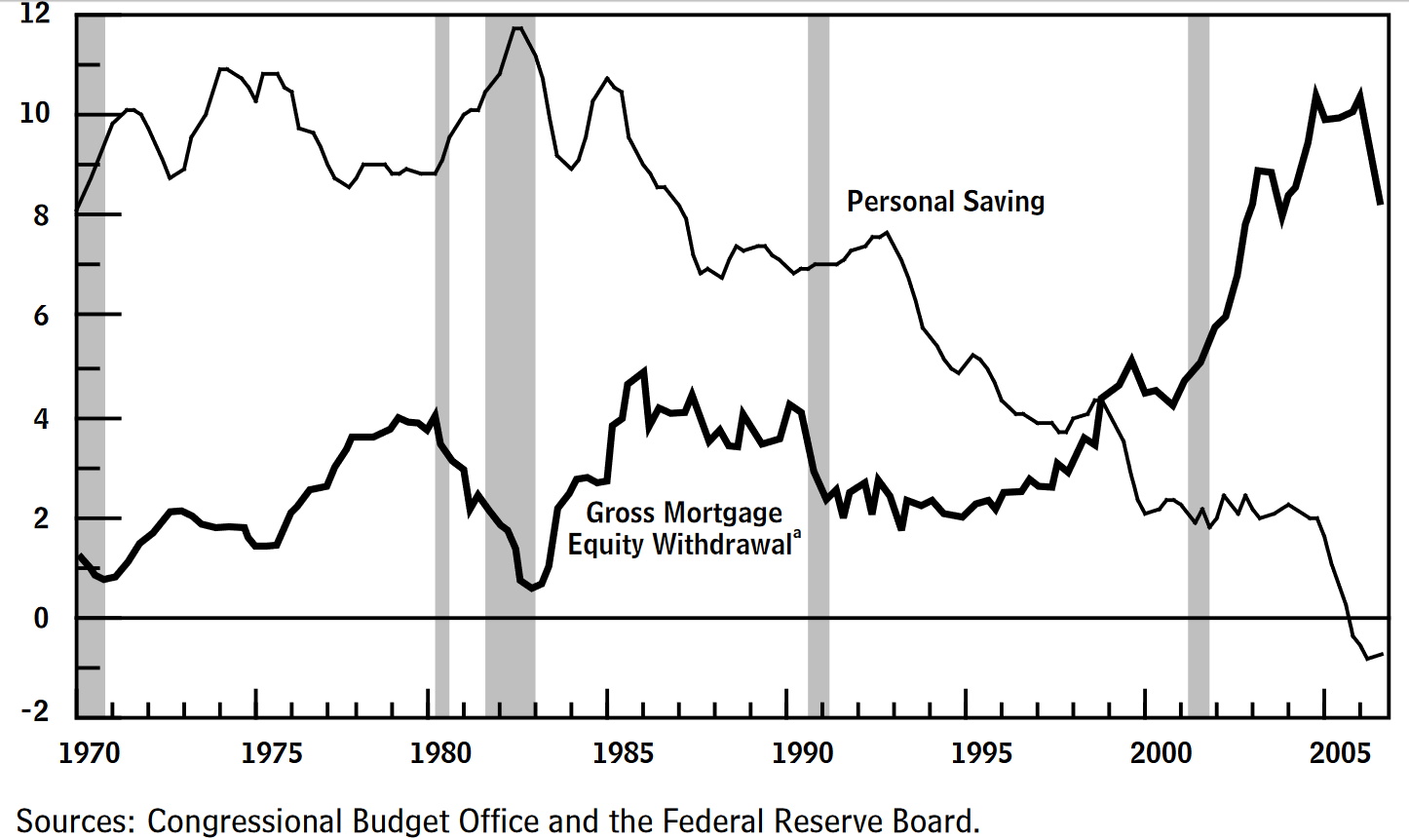

1982, the year following Reagan’s Economic Recovery Tax Act, simultaneously saw a 35-year high for personal savings and 35-year low for mortgage equity withdrawal (MEW), as a percentage of disposable income. By 2005, these lows and highs had flipped. Figure 3.1 shows this outstanding inverse relationship between the ratios of personal saving and MEW to disposable income. Additionally, Mian and Sufi124 “House Prices, Home Equity-Based Borrowing, and the US Household Leverage Crisis.” found that, as a home increased in value, that household invested less elsewhere. While estimates vary on the uses of extracted mortgage equity that funds personal consumption,125 Per Alan Greenspan and James Kennedy, “Sources and Uses of Equity Extracted from Homes,” Working Paper (Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board, March 2007), estimates range from 1% to over 50% of gross mortgage equity withdrawn. it is clear that homeowners use funds to pay down debt and renovate their homes. In other words, understandings of housing as an asset are not foreign to homeowners, especially those who bought in the crest of that Minsky cycle. Homeowners who bought in between 1999 and 2005 saw median net worth jump “from $11,000 to $88,000 in real terms, driven largely by rising home equity.”126 Schwartz and Seabrooke, The Politics of Housing Booms and Busts.

Figure 3.1: Personal saving and mortgage equity withdrawal as a percentage of disposable income.

While these consumption effects are not unique to housing, they are most significant in housing. Mortgage equity exhibits greater wealth effects than investments in stocks: research by Karl E. Case, John M. Quigley, and Robert J. Shiller127 “Comparing Wealth Effects: The Stock Market Versus the Housing Market,” Advances in Macroeconomics 5, no. 1 (2005), https://doi.org/10.2202/1534-6013.1235. found statistically-significant increases in the consumption patterns of housing wealth over stock market wealth. Specifically, every new dollar of housing income generated 6 cents of new consumption over the same dollar in stock market income. Economists disagree as to the cause and level of this wealth effect, but its primacy over other financial holdings is broadly agreed upon,128 Mark Lasky and Andrew Gisselquist, “Housing Wealth and Consumer Spending” (Congressional Budget Office, January 2007). and fits into the view that America has transitioned into a consumption- and import-oriented economy. Compounding the significance of housing wealth was the sheer size and volatility of housing: Ansell notes that, “between 1985 and 2006, real house price inflation was three times greater than between 1970 and 1985, with a standard deviation almost twice as large.”129 Ansell, “The Political Economy of Ownership,” 383. And MEW increased from $300 billion annually between 1991 and 2000 to $1 trillion between 2001 and 2005.130 Schwartz, Subprime Nation, 100.

Subsidizing housing and home mortgages privatizes government spending otherwise recognizable as welfare. In doing so, the policies and implementations change how citizens view the state’s role in their personal finances. More specifically, individuals’ preferences for welfare depend “on how existing policies shape their experience of individual risk.”131 Jane Gingrich and Ben Ansell, “Preferences in Context: Micro Preferences, Macro Contexts, and the Demand for Social Policy,” Comparative Political Studies 45, no. 12 (December 2012): 1624–54, https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012463904. A stronger claim would be that policies train beneficiaries, a view held by Isaac William Martin. He uses this mechanism to explain the great political diversity of organizers for Proposition 13 in California: homeowners protect the welfare afforded to them.132 Martin, “Welcome to the Tax Cutting Party.” At the local level, homeowners have long lobbied as a class, enclosing their neighborhoods from Black applicants, breaking calls for more affordable up-zoning, and rejecting industry that would be welcome five miles away. It should come as no surprise that homeowners react to direct and indirect subsidies in similar ways as they react to market-caused fluctuations in their home values.

By privatizing government spending, the subsidies offered by the Neighborhood Stabilization Program individualized housing gains, differentiating this form of “invisible welfare” from the more visible welfare programs debated by the Republican and Democratic parties. Visible welfare programs transfer individual risk to social risk,133 Gingrich and Ansell, “Preferences in Context.” and make more equitable134 Monica Prasad, The Land of Too Much: American Abundance and the Paradox of Poverty (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012), 229. the public goods of a society (in the Rawlsian sense). These two features distinguish the welfare that is argued about on television from the welfare that is argued about in journals. The political scientist’s point is that they are substitutable: preference for this private form of insurance reduces the demand for social insurance programs.

Then, the task for the individual political actor is simply to follow these preferences to their political implications by stepping back through the argument in Chapter 2. This argument says that, under the narrative of balanced budgets and concerns over the national debt, lower expenditure makes possible lower revenue. Therefore, lower preference for social insurance justifies preferences for lower taxation. Additionally, early research by Frank Castles and Jim Kemeny suggest that downpayments and mortgages factor into household expenditures early, while property taxes are considered only after necessary expenses have been paid.135 Schwartz and Seabrooke, The Politics of Housing Booms and Busts, 13. Tea Party candidates then, merely augmented this aversion to taxes with a political logic, clearing a spot for the preferences of privately-insured, but tax-burdened voters.

However, it is important to understand that, just like the contingencies of party platforms, there are contingencies in how individuals process economic data and political propositions. Larry M. Bartels136 “Beyond the Running Tally: Partisan Bias in Political Perceptions,” Political Behavior 24, no. 2 (2002): 117–50. accepts this basic assumption while rejecting the idea that ideology or partisanship are static filters through which people see selectively. Rather, he argues, partisanship is a dynamic negotiation between partisanship as exogenous or endogenous variable. His Bayesian learning model presents a different model: people update beliefs as new information becomes available, but people also selectively intake information according to beliefs. Disentangling the two sub-routines is difficult, if not impossible, but the rule of thumb is that long-held beliefs require [relatively] huge inconsistencies to catalyze change.

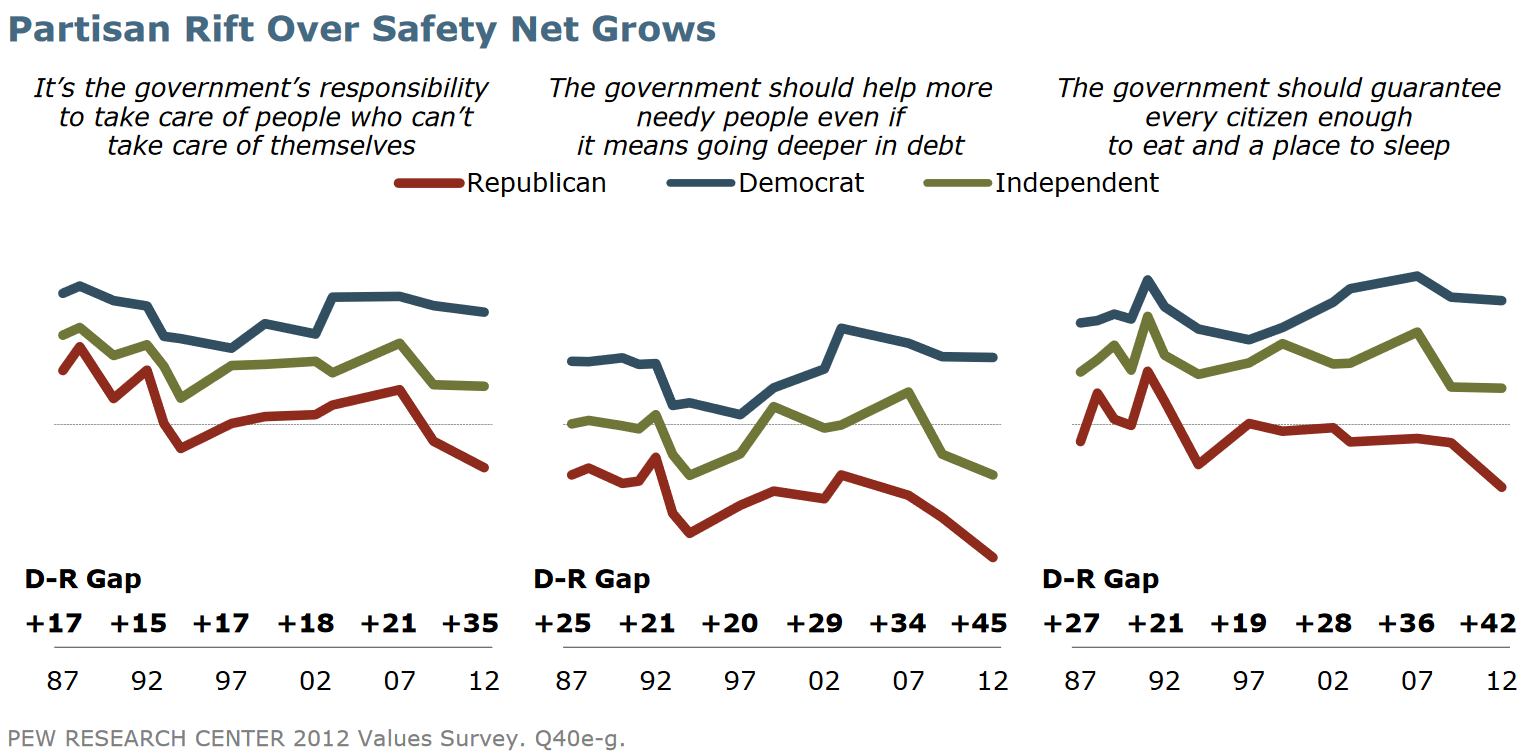

While the mortgage crisis, financial meltdown, and ensuing Great Recession delivered onto unsuspecting citizens heaps of information—much of it likely inconsistent with individual beliefs about meritocracy, personal financial stability, and government oversight—survey data suggests that the government response delivered similarly-sized heaps of information. Pew Research’s American Values polling series has tracked opposition and support of various political positions since the late 1980s.137 Andrew Kohut et al., “Partisan Polarization Surges in Bush, Obama Years” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, June 2012). This longitudinal surveying shows sharp a divergence between the economic beliefs of Democrats and Republicans as well as between independents who lean either way. For partisan divides, Figure 3.2 shows how Republican beliefs regarding social insurance regress to a conservative ideal more aggressively than both Democrats and independents. I split hairs over this behavior with Ansell (2014), who maintains it is self-identifying liberals who maintain an ideological opposition to spending cuts.138 Ansell, “The Political Economy of Ownership,” 387. This position is not exactly borne out in the Pew numbers: while independent support for raising social insurance spending (middle panel) falls relative to Democratic support after 2007, independent support for maintaining (left panel) or expanding (right panel) social insurance spending when disconnected from budgetary imbalances hews closely to Democratic behavior. When these are combined with the polling on ideological slant, the Pew research offers a coherent picture of independent voting behavior between 2007 and 2012.

Figure 3.2: Support for social insurance programs by party.

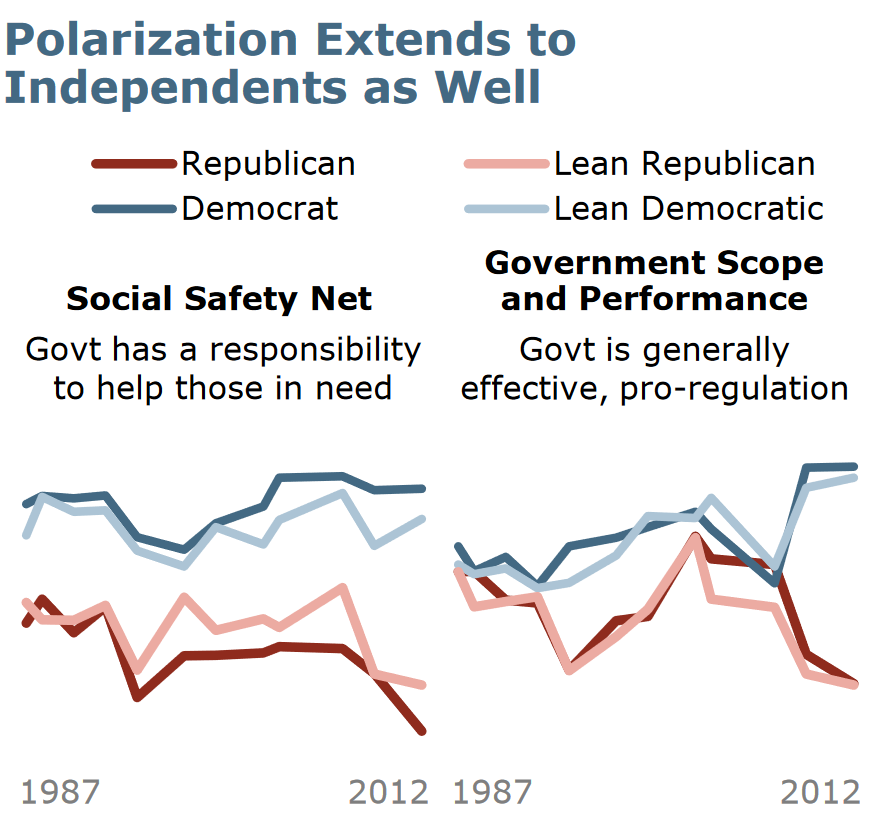

Figure 3.3 shows how independents who lean towards a party compare with those parties on a number of political positions. The larger variance in positions for both sets of “leaners” shows how independents less consistently assimilate perceptions of evolving economic realities into their political positions. Those who identify as Republicans or Democrats are not swayed in their support for social safety net provisions by the eruption of financial and economic turmoil. In contrast, leaners towards both parties are strongly affected by its event, and even more strongly affected by the subsequent increase in spending and its surrounding rhetoric. Partisanship affects how individuals fit economic perceptions into their political positions; not all voters could (let alone would) be affected by something like rising home prices. Therefore, my model aims at marginal voters, those independents whose picture of the world is more open to alteration. “But,” as Schwartz notes with regard to the election of Barack Obama, “a shift in the votes of only 5–10 percent of voters can be electorally decisive, and by late 2008 one-sixth of U.S. homeowners had negative equity.”139 Schwartz, Subprime Nation, 178.

Figure 3.3: Support for social insurance programs by ideology.

Figure 3.3: Support for social insurance programs by ideology.

And I expect the effects to be marginal, as the Neighborhood Stabilization Program likely enriched no one by 2010. If each foreclosure costs, on average, $159,000 in decreased property values,140 Immergluck, Foreclosed, 151. then each surrounding home value decreases by only a fraction of that number. Conversely, if a vacant property is fixed and resold, surrounding home values would only increase by a fraction. Additionally, the hefty oversight on the NSP targeted profiteering by local actors, preventing any get-rich-quick schemes. The Neighborhood Stabilization Program receives high marks methodologically from its under-the-radar nature: if voters knew, and could filter, their wealth gains through an ideological sieve, it could skew results. Rather, its small effects and lack of advertising141 Anne Gass, “Guide to Marketing and Selling NSP Homes” (Department of Housing and Urban Development, July 2010), 5. (matched by equally-tiny press coverage) simplify an analysis that would otherwise seek to account for the media narrative surrounding such a program.

While these factors simplify my analysis and attenuate its potential for strong conclusions, my model is complicated by the way that humans value equal amounts of money lost and gained. In behavioral economics and cognitive psychology, the endowment effect describes the premium that individuals place on ownership. Asked to trade one object given to them for another of equivalent exchange value, people demonstrate a marked preference for the object assigned to them. The endowment effect is tied to loss aversion, which is that people experience a dollar lost much more acutely than a dollar gained.142 Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler, “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (March 1991): 193–206, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.193. In the permanent income hypothesis, this behavior is not well integrated. Even with “buffer shocks” added in, the hypothesis asserts that wealth shocks will affect spending linearly.

To give a concrete example, consider a home worth $100,000 in 2000. If that home increased in value $50,000, a marginal propensity to consume (MPC)—the economist’s term for the extra spending per dollar—of .06 would predict that \(.06 \times \$50,000 = \$3,000\) of extra consumption would result. However, what if that home decreased in value $50,000? Would spending decrease $3,000? It seems unlikely that, in the midst of an event labeled as a ‘crisis’ or the ‘Great Recession’, spending would not decrease even more dramatically, and would be reluctant to rise for fear that momentary gains would be washed away by another crashing wave of home prices. Or, maybe contractions exhibit a linear relationship with the rate of price changes, but a different relationship results from the endowment effect. In this second case, consumption is a function not only of price changes, but also of net positions: a homeowner spends freely so long as their home is worth more than their original purchase price, but is averse or highly-sensitive to dips below the original price.

Angrisani, Hurd, & Rohwedder (2019) demonstrated that the marginal propensity to consume changed during the recession (2008–2010) from its run-up (2005–2008). That these dates do not align perfectly with those of the foreclosure crisis (2007–2012) is not significant; these dates contain the three phases of the Neighborhood Stabilization Program as well as the 2010 midterms, and overlap significantly with the foreclosure crisis. They used an instrumental variables approach to estimate the MPC of non-recessionary periods to be statistically insignificant, while that of the recession to be 0.062.143 Marco Angrisani, Michael Hurd, and Susann Rohwedder, “The Effect of Housing Wealth Losses on Spending in the Great Recession,” Economic Inquiry 57, no. 2 (April 2019): 986, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12753. His finding that non-recessionary periods exhibit no change in marginal propensity to consume conforms to the rational expectations model of microeconomic behavior—given an expected change in income, individuals will not alter consumption. Rather, it is only during an unexpected change in expectations (such as a recession) that consumption changes. This understanding integrates Angrisani, Hurd, & Rohwedder’s research with most of the work on housing wealth effects pre- and post-crisis.144 Greenspan and Kennedy, “Sources and Uses of Equity Extracted from Homes”; Lasky and Gisselquist, “Housing Wealth and Consumer Spending”; Mian, Sufi, and Trebbi, “The Political Economy of the US Mortgage Default Crisis”; Schwartz, Subprime Nation.

Their findings are buttressed by two other pieces of literature. The first is the body of work on endowment effects and the psychological costs of loss versus gain. Angrisani et al. acknowledges this by saying “If, as documented in previous work, wealth losses are more likely to induce changes in behavior than gains, our estimates may reflect a more pronounced sensitivity of household spending to falling house values.”145 Angrisani, Hurd, and Rohwedder, “The Effect of Housing Wealth Losses on Spending in the Great Recession,” 987. The second paper understands data that points to large consumption effects as running contrary to the permanent income hypothesis, which predicts that wealth shocks will be amortized over an individuals’ lifetime. It then builds a new model that attempts to model homeowner expectations based on realistic features of the housing market such as debt levels, collateralization, and variable home price expectations. These features result in larger marginal propensities to consume, and larger effects of lost wealth than gained wealth.146 David Berger et al., “House Prices and Consumer Spending,” Working Paper, November 2016.

The upshot this literature yields for my analysis is that neighborhoods not targeted by the Neighborhood Stabilization Program should see consumption decrease meaningfully. This behavior should heighten labor market risk, meaning that, in untargeted areas, lower Republican support should be present. An additional—but less controversial—tension to consider is the relationship between change of wealth and total position of wealth. In general, the marginal propensity of wealth decreases as individuals get wealthier.147 Luc Arrondel, Pierre Lamarche, and Frédérique Savignac, “Wealth Effects on Consumption Across the Wealth Distribution: Empirical Evidence,” Working Paper (Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, June 2015). While there is some squirreliness regarding housing MPC at the very high end of the wealth distribution (second and third homes may truly be just assets, so the purpose would be extra consumption), given the size and location of such high wealth individuals, it is unlikely the Neighborhood Stabilization Program affected those individuals’ houses. This result implies that those tracts targeted by the NSP should be especially sensitive to its marginal price increases (or decreases) and therefore exhibit higher (or lower) Republican voting returns.

3.2 Control Variables

I turn now to more general models of American congressional voting. Little is made of the controlling variables in academic publications, but anyone who has toyed around with regression analysis knows that the exclusion or inclusion of one or two variables can make or break statistical significance, and the acceptance that comes with that standard. Often variables are included without explanation, leading to suspicions about the robustness of statistical inference. It is therefore important to offer multiple ways for readers to inspect one’s work. The first way is to explain the inclusion—or sometimes, exclusion—of particular variables used to disaggregate the effects of contributory forces. The second way, shown in the next chapter, is to present analyses that include or exclude particular variables; then differences, if they are significant, can decompose a particular effect. For instance, the NSP supposedly has a positive effect on prices. Then, when looking at the differences between a regression of Republican voting on tracts designated as NSP without taking into account price changes and a regression with price changes included, the difference in the coefficients between the two trials should show how much of the NSP’s effects on voting were due to its influence on prices.

It is important to isolate the effects of the Neighborhood Stabilization Program. To do so, I will include several variables that may covary with both NSP allocations—defined by risk of further foreclosure—and Republican voting behavior. These variables are lumped into three broad categories: visible identity, including race and age; economic identity, including income and unemployment; and cultural identity, including measures of urbanicity as well as religion. This breakdown acts purely for organizational purposes as the blur between visible, economic, and cultural should make clear, but they nonetheless reflect a view that voting decisions can be reduced to observable characteristics. Absent individual polling, the demographic features provided by the decennial census offer the best chance at understanding voter behavior.

3.2.1 Visible Identity

Visible identities are those which are involuntarily imposed. They press, as Kwame Anthony Appiah, notes, as “walls that hedge us in.”148 Kwame Anthony Appiah, The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity, eBook (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2018), 189. Since many of these identities have become legally protected categories in the United States, their records are kept precisely and publicly. The upshot of this feature is that records are easily available, but this availability may lead to an overestimation of their effects on voting, as researchers look where the light shines instead of where their object of interest may be found. On the other hand, while partisan voting support may have counter-intuitive logic that necessitates complex research methodologies, rational explanations for identity-based support are often at hand in visible identities.

For instance, Black voters long supported the Republican Party as the party of Abraham Lincoln, the nation’s first Black legislators, and as proponents of programs benefitting African Americans. This support changed first with the New Deal, with Franklin Delano Roosevelt won 71% of the votes cast by African Americans in 1936, though party identification by African Americans remained even between the two parties over the next ten years. During the Civil Rights Movement this support changed again, when votes for Lyndon B. Johnson’s first elected term commanded 94% of the Black vote.149 Brooks Jackson, “Blacks and the Democratic Party,” FactCheck.org, April 2008. Some of the United States’ pre-eminent segregationists were staunch Democrats, but federal action by Lyndon B. Johnson and subsequent campaigning by Richard Nixon effectively fractured Democratic support in the South. In the contemporary Democratic Party, redistributionist welfare programs aligned with integration to remedy both the economic and social disparities between white and Black Americans, turning the Democratic Party towards the majority of African Americans.

Similar stories cannot be told for American Indians, Asian Americans, or ethnically Hispanic Americans, but each has their own story with the Republican or Democratic parties. While the American Indians vote swings heavily Democratic, very few of the tracts in my dataset have significant populations, a fact also owing to their legal disenfranchisement and decimation by civilian and military forces. Even as reservation residents disproportionately receive cash or food stamps from the federal government compared with households in the general population,150 “Public Assistance Income or Food Stamps/SNAP in the Past 12 Months for Households” (US Census Bureau, 2010). I will not consider the effects of American Indian population in my analysis due to their diffusion throughout my sample and low turnout rates.

The stories of Asian Americans and ethnically Hispanic Americans are perhaps the most fractured among racial political narratives. The “Hispanic vote” is often pointed to as a core aspirational piece of the Democratic coalition, though Democratic candidates maintain a checkered record in attracting and serving ethnically Hispanic voters. Nonetheless, there are compelling reasons to include a measure of Hispanic voters. Until a certain point, an increased Hispanic population raises fears of white job loss, increasing conservative—and especially Tea Party—voting, though no consensus regarding this “racial threat” hypothesis has emerged.151 Andrea Louise Campbell, Cara Wong, and Jack Citrin, “‘Racial Threat’, Partisan Climate, and Direct Democracy: Contextual Effects in Three California Initiatives,” Political Behavior 28, no. 2 (June 2006): 129, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-006-9005-6. As white voters compose between 60% and 70% of the national electorate, fears inflected through them lead to significant effects.

Additionally, Hispanic and Latinx people were integral to both the political and financial nature of early-2000s housing. Republicans used housing policy as a way to attract Hispanic voters. With more than 50% of Hispanic people living in America identifying themselves as Catholic,152 “The Shifting Religious Identity of Latinos in the United States,” Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project, May 2014. adding the promise of a home to conservative social values would further cement the 40% of the “Hispanic vote” achieved by Republicans in the 2004 presidential election.153 Marisa A. Abrajano, R. Michael Alvarez, and Jonathan Nagler, “The Hispanic Vote in the 2004 Presidential Election: Insecurity and Moral Concerns,” The Journal of Politics 70, no. 2 (April 2008): 368–82, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080365. Conversely, Adam Tooze notes that “Democrats had a lot riding” on the rise of Black and Latinx middle classes.154 Tooze, Crashed, 47. Whichever way the needle points, Hispanic voters were important features of the electorate. On the financial side, “Latinos were more likely and Asians less likely to receive subprime loans than whites were.”155 Jacob W. Faber, “Racial Dynamics of Subprime Mortgage Lending at the Peak,” Housing Policy Debate 23, no. 2 (April 2013): 328, https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2013.771788.

While Asian Americans are certainly implicated in the mortgage lending processes that affected NSP allocations, there are huge fractures within Asian American communities that complicate expectations of national partisanship. Asian-American commenters have pushed back against the “Model Minority” myth to contextualize the fact that the median Asian American income earner—come their families (or they) from India, China, Vietnam, Japan, Korea, Iran, Uzbekistan, or the Philippines—made in 2016 $3,330 more than the average white household. But inequality among Asian Americans is worse than for any other group; Pew notes that income earners in the 90th percentile made nearly 11 times as much as those in the 10th percentile.156 Rakesh Kochhar and Anthony Cilluffo, “Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians,” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project, July 2018. I include Asian-American portion of voters for much the same reason as I include Hispanic portion: while indeterminate, Asian Americans (at times homogenized in such terms by politicians) were differentially implicated in mortgage lending and politics.

Lastly, age comes into play as a proxy for an invisible identity, that of retiree. Fixed-income voters are highly sensitive to home price increases, because home equity can be the only variable piece of their budget. Additionally, a wealth change amortized over a shorter lifespan will present as higher average income, and therefore consumption. Rather than use the median or average age of the U.S. population, the decennial Census tracks the number of people in five-year bins. Therefore, I use the percentage of people 65 years of age or older to estimate the amount of retirees (or those whose thoughts are largely on retirement). Ideally, these forces could be disentangled with microdata on labor force participation, which could distinguish a retiree from merely an old person, but nationwide data by age do not exist on the local level.

3.2.2 Economic Identity

A key feature of the housing-as-insurance model is the lever of labor market risk. Labor market risk acts to increase the demand for insurance. Home equity can replace welfare programs when unstable employment is present. We should thus expect that higher levels of these two factors magnify the effects of price changes. Specifically, price increases—which Ansell’s research has shown dampens demand for social insurance policies—should have even greater conservatizing effects when refracted through high employment risk or low equity (proxied by the foreclosure rate). If home equity acts as a buffer against lost wages, then lower levels of home equity make individuals more sensitive to price shocks just as lower employment expectations would shift the income-generating burden onto housing speculation. Regression techniques known as interaction effects can calculate how variables—in this case, labor market risk or foreclosure rates paired with recent price changes—refract through one another. In this analysis, the interactions between labor market risk, foreclosure rates, and price changes should be significant and positive, regardless of the coefficients attached to labor market risk and foreclosure rates.

To measure labor market risk, I took the variance of monthly unemployment rates from 2005 to 2010 for every sampled county. This value is an index of gross changes in unemployment, separate from whether such a county is currently in a employment glut or rut, an aspect captured by the net change in unemployment from 2005 to 2010, as well as the level of unemployment in 2010. The foreclosure rate is a key piece of the labor risk–equity model, as high foreclosure rates depress prices of surrounding homes, shrinking the amount of equity much as a declining stock price shrinks the value of individual portfolios holding said stock. As described in Chapters 1 and 2, foreclosures may also trigger animosity among neighbors, who label dispossessed homeowners as “deadbeats”. Since foreclosures play directly into the allocation formula for the NSP, as well as possibly into Republican voting, the foreclosure rate is an important covariate to include in this analysis.

A possible—though not thoroughly supported—connection between length of tenure in home and conservative preferences leads me to include it as well as its square. The longer someone lives in a single area, the less they may come in contact with conditions, ideas, people outside that local area, and could indicate that they believe their place of residence to be in no need of change. While these lines of reasoning connect tenure to Republican voting, they do not account for their connection to the NSP. The formula allocation takes into account the amount of high-cost, high-leverage mortgages in an area. Someone who moved into their home in 1969 would be unlikely to have a mortgage at all, let alone a subprime mortgage. One should expect relatively few mortgages held by people who have lived in the same residence for more than 30 years, but conservative effects as outlined above. Conversely, recent residents may be highly-leveraged, recently employed, and highly-susceptible to price changes. So tenure may be positively associated in its square term with Republican voting but negatively associated linearly. Additionally, I included median household income to control for variations in class.

3.2.3 Cultural Identity

Three primary factors flavor voting at the cultural level: religion, urbanicity, and highest level of education attained. Within these factors, which are so grouped because they are in some sense voluntarily elected by the person to which the characteristics are attached, specific levels are significantly associated with Republican voting, while other levels are a mixed bag. Religion exemplifies this relationship. Republican voting by evangelical Protestants and members of the Church of Latter-Day Saints (L.D.S., or the Mormon Church) is much more predictable than voting by members adherent to any religion,157 “A Deep Dive into Party Affiliation,” Pew Research Center’s U.S. Politics & Policy Project, April 2015. while prior literature has identified household factors—namely size, and age of parents—that push Mormon applicants to become early, unqualified entrants to the mortgage market, and therefore more susceptible to application rejections and subprime lending.158 Jean M. Lown, “Educating and Empowering Consumers to Avoid Bankruptcy,” International Journal of Consumer Studies 29, no. 5 (2005): 401–8, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00468.x. While that analysis was conducted exclusively on L.D.S. adherents, the logic extends as well to evangelical adherents, prompting the inclusion of both. The U.S. Religion Census reports county-level data on adherents to a huge number of denominations, and is the only sub-national source for all fifty states. Conducted contemporaneously with the decennial census (though not connected, organizationally), I will join county-level statistics regarding the level of evangelical Protestants and L.D.S. adherents to the census tract–level.

Additionally, the urban-rural divide has been noted as a political cleavage. Lower-density areas provide fewer international transportation options, educational/translation resources, and less name recognition than do large cities. The populations of many rural areas is implicitly limited by agricultural or industrial land holdings that prevent large turnover of residents. And on the side of push factors, residents of rural areas are often more religious than their urban counterparts, find traditional social institutions more important, and are generally older than cities and suburbs. These factors do not imply that those areas are in stasis, but rather that the rigidity of beliefs is compounded by the institutions and political economy of rural areas. These beliefs, in long historical sweep, are generally better represented by conservative legislators currently residing in the Republican party.

Additionally, the highest level of education attained is a huge predictor of one’s party affiliation, but only for white voters. A 15-point gap persists between white voters with and without a college degree: 45% percent of college-educated white voters cast their ballots for Republicans, while more than 60% of those with a college degree did the same.159 Adam Harris, “America Is Divided by Education,” The Atlantic (https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/11/education-gap-explains-american-politics/575113/, November 2018). This trait has intensified since George H. W. Bush’s presidency, before which educated and uneducated voters were more or less aligned. I weight the importance of this variable by its frequency: a tract with a single white voter who is not college educated is far less significant than one with 2,000 white voters, 45% of whom are not college educated.

Lastly, I attempted to deal with the specific political circumstances of each state. Usually, the strategy would be to include state-level fixed effects, which essentially groups a state together and tries to explain inter-state variations. However, adopting this strategy may bias my results in two ways. First, connecting votes to specific precincts (as I will detail in Section 4.2) was fraught with local variations in naming conventions. This meant that available data congregated in specific counties or cities that adopted standard naming conventions, which often were large cities and counties with well-staffed registrar offices. Since home prices are so local, and more populous cities and counties often denser, this irregularity of errors could bias particular states’ fixed effects such that a fixed-effects term captures some of the price-change variation rather than the political content of that state.

Second, home price data were only available in tracts which saw greater than 100 sales (and correlative purchases). As such, tracts that were particularly populous, highly transient, with high owner-occupancy rates, or saw large price swings (triggering sell-offs) are disproportionately represented in the data. These features should generally bias the data in a similar way as vote-return availability, and a state fixed-effect term would captures some of this variation. Instead, I use the 2008 Cook Partisan Voting Index (PVI) to measure state-level politics. In a nation-wide voting sample, a fixed effects term and the PVI should be similar. But with a limited sample, this nationwide measure is more appropriate. The Cook PVI takes the difference of a state’s vote margin for a presidential candidate with the national vote margin. For instance, John McCain won 46.3% of the national popular vote in 2008. Since Virginia went 46.8% for McCain, its 2008 Cook PVI would be +.5; Massachusetts, on the other hand, went 36.8% for McCain, giving it a 2008 PVI of -9.5.

3.3 A Model of Voting

The discussion above leaves me with a model of Republican voting:

\[\begin{multline} rep_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1NSP_i + \beta_2(PriceChg_i \times ForeclosureRate_i) + \\ \beta_3(PriceChg_i \times LaborRisk_i) + \beta_4UnemploymentChg_i + \beta_5medHHI_i + \\ \beta_6Density_i + \beta_7Tenure_i + \beta_8Tenure^2_i + \beta_9Old_i + \beta_{10}Black_i + \beta_{11}Hispanic_i + \\ \beta_{12}Hispanic^2_i + \beta_{13}Asian + \beta_{13}(White_i + SomeCol_i) + \beta_{13}Evangelical_i + \beta_{14}LDS_i + \beta_{15}PVI_i + \epsilon_i \tag{3.1} \end{multline}\]