Edit 10/20/2019: check this article out at Pop Culture Bento!

Hitchcock’s cinematographic style changes with each script and year in which he immerses himself, unlike the storybook qualities of Wes Anderson or the placid Drops dripped of Andrei Tarkovsky. Vertigo, at the dizzying heights of Hitchcock’s mastery, leads us into John Ferguson’s (James Stewart) mind—distorted by the lethal, dozen-story fall of a partner trying to save Ferguson—by forcing us into cramped spaces and mocking our spatial judgment. I argue that in doing so, Hitchcock forces viewers to understand the disorientation and claustrophobia that Ferguson so clearly feels. In doing so, Hitchcock makes reasonable the otherwise unreasonable male gaze of Ferguson and, by association, the effects that gaze causes, though it’s unclear whether it serves to morally justify that gaze. So, in-movie, Hitchcock uses film technique to warp what would otherwise be a black-and-white judgment about Ferguson’s behavior towards Judy Barton (Kim Novak). Out-of-movie, I finally make the claim that this in-movie phenomenon critiques white American masculinity’s treatment of the Other.

Much of this analysis was impossible for me until I considered David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive—there were too many motifs in Vertigo to grab a hold of! Hitchcock employs a contrasting color palette, his signature(ly disturbing) perplexion with blonde women, and an unforgettable break in narrative. Mulholland offers those motifs amped up to surrealistic proportions, with color palettes at near antagonistic levels, the blondes shining ever more platinum, though its narrative break is difficult to pinpoint. Connecting Mulholland Drive and Vertigo makes the interpretation of Hitchcock’s film no easier, but facilitates a shift in mindset that rendered Vertigo much more interpretable.

I mean this: Lynch is enigmatic as hell, but he continues to give interviews. In these interviews, he surrenders much of his creativity to what he terms “dream-logic”, and it stands out immediately. Dream-logic connects two objects despite their inconsistencies according to logic-logic. Such an approach finds its Western roots entirely recent, coming primarily out of Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. Its epistemology is usually visual in [Lynch’s] movies, though connections via homonym or punnery are entirely within the bounds of Freudian analysis. While a novelty in 2001 Mulholland Drive premiered, 1958 saw psychoanalysis at its peak of influence. This rise crashed into Hitchcock’s prior work with film noir, convoluted plots that often involved damaged detectives and female subjects vulnerable physically and mentally.

Vertigo synthesizes these two strands. Kim Novak’s characters—one before, one after the narrative break—vie for their freedom against their supposed history. In classic Hitchcock fashion, Vertigo can be summarized as a Wrong Man Film,1 where the protagonist is mistaken for a doppelgänger implicated in deep, deep shit. Unclassically, Vertigo’s protagonist is no man; and its protagonist(s) is/are not its central character(s). Novak’s Judy Barton is modeled (mostly) against her will after a prior, dead San Francisco socialite, Madeleine Ester,2 who herself models a [much more] prior, dead San Francisco socialite. The complicity of each in creating their respective iron cloaks of identity is uncertain, but beside the point—Ferguson’s male gaze visualizes these identities before they are realized.

Often enough, the male gaze is analyzed as a whole, apart from its sometimes very specific set of eyes. I get at Ferguson’s specific set through Hitchcock’s motifs and cinematography. Ferguson’s gaze is set very literally in the film’s opening. Hitchcock shakes up the presumably keen vision of a detective with his partner’s death. The fall and the height and the guilt confuse themselves in Ferguson’s head to deliver a crippling case of vertigo, rendering him unproductive and idle, unmoored from his former senses of intelligence. There is nothing objective against which Ferguson can mark the damage his trauma wrought, no other detectives to which he can compare.

Hitchock will signify this psychosis slowly at first, then all at once. This chronological pattern approximates the spiral imagery so fundamental to Vertigo. Saul Bass’ iconic movie poster design depicts Ferguson plunging into a line-drawn spiral. This third dimension is added, and reflects the way objects track in wide-diameter circles, speeding as the circles shrink and finally encloses the object.3 Concerned of the obsession his wife (Madeleine) exhibits for a suicidal ancestor, Ferguson’s friend sends him to play private detective. While Scottie takes logical steps to follow the wife’s story, his social isolation and physical trauma get the better of him. His steps culminate in a famous leap into the brisk San Francisco Bay, where, just before, Madeleine plunged, unconscious.

After the dive in, James Ferguson can never quite get himself on solid ground. The spiral patterns begin to crop up in paintings, department stores, cemeteries, etc.

Caught in the inner circles of a deepening plot and deepening conspiracy, Hitchcock simulates what Ferguson’s deepening psychosis4 must feel like with cinematographic trickery that encloses Ferguson’s figure, disclosing the craze lurking inside his obsessed mind. In Vertigo’s camerawork, deep focus and a 2-D plane forces our visual cortex to compare the near and far. The video below demonstrates this several times.

Those yellow flowers that Scottie walks behind at 1:59 appear taller than him in that moment, and the obscured view traps his figure in the history, mystery, and death that linger after Novak exits the scene. Hitchcock further unsettles viewers in :17, not with the normal technique of a dolly following Ferguson and suggesting danger, but with a shot from below. This camera setting exaggerates the height and length of objects outside focal point, making the 3ft flowers equal the 6ft Ferguson in height. The mastery here is the unresolved tension between these instances of camera trickery and Hitchcock’s concurrent attention to truly large objects. The enormity of the Golden Gate bridge in one famous shot anchors the nearly surreal imagery elsewhere in Vertigo, cementing a permanent unease.

Add this to the geologic folding that turns ordinary car following into labyrinthine mazes:

And of course, Vertigo’s signature camera effect, the zoom-in/dolly-out:

The spirals (2:13), the huge objects (:36), the zoom-in/dolly-out (1:20) culminate in Vertigo’s quasi-climax:

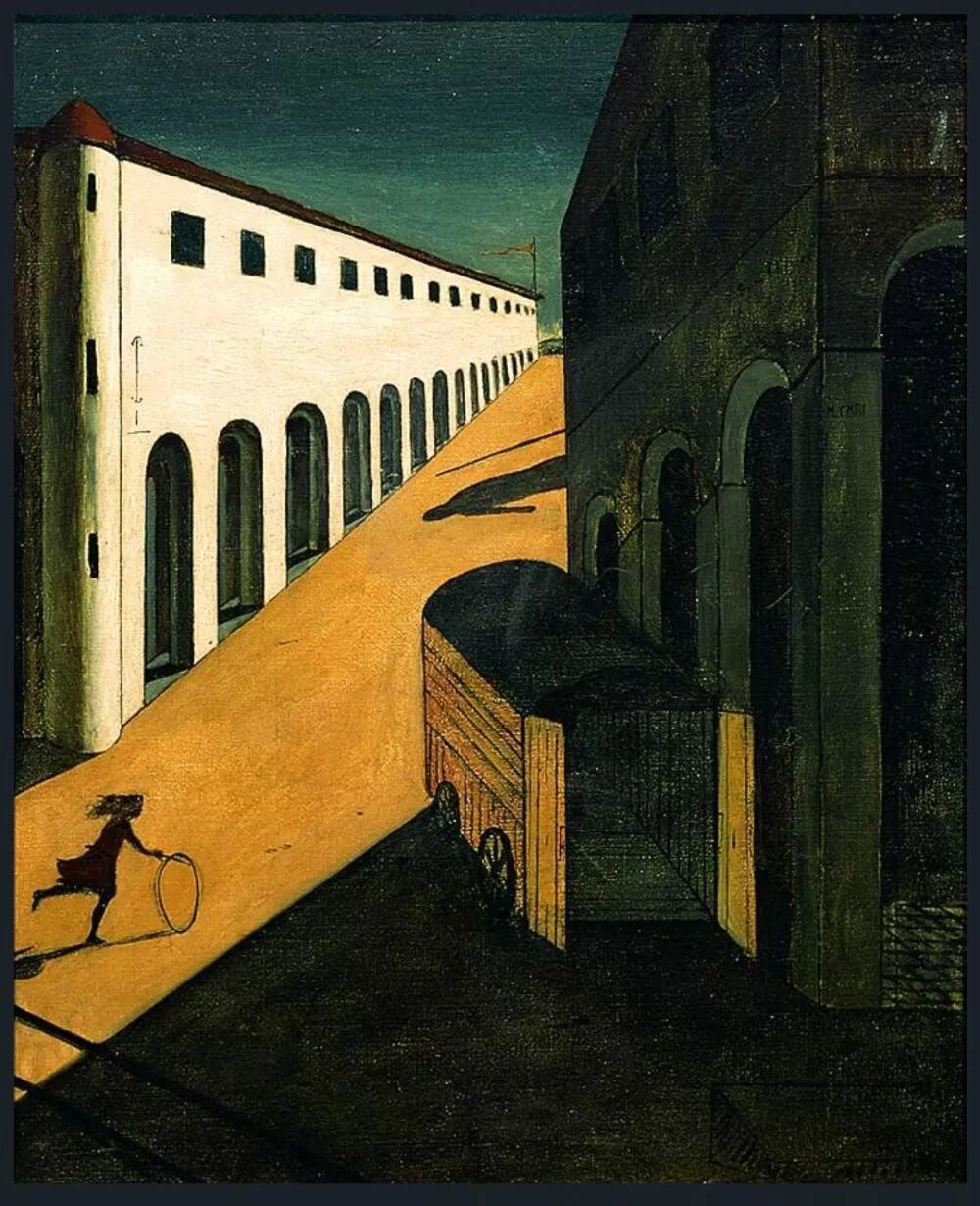

The scene in Mission San Juan Bautista also bears striking resemblances to the work of Italian surrealist Giorgio de Chirico. De Chirico’s work produces a sense of unease through its emphasis on the uncanny, that which is not quite and yet almost is. I like to think of a composite image, the subimages of which are all perfectly possible, though the composite somehow not being possible. In the image below, which reminds me both of the Mission and the ever-out-of-reach Madeleine, the sky is a natural color for sunsets and the long shadows possible at twilight, but the building is so bright and the shadows so stark that the image could not possibly depict a real event. Hitchcock, toeing the sur/realism line, never leaves us with quite the uncanny images or impossible geometries to prove the sort of dream-logic that Lynch would make explicit, but these scenes add up. With snaking streets, out-of-proportion objects, and color palette, builds a profile of the uncanny without ever letting us put a finger on it. Like Ferguson, the viewer is hard-pressed to resolve the visual inputs Hitchcock offers.

This kind of confusion invites resolution for the viewer into a reality-less vacuum. Similarly, while Ferguson is a detective, used to getting to the Bottom of Things, he can’t in this situation. All his preternatural detective powers have been duped by trauma and deceit. He is painfully aware which way is up and which down, but not much beyond that. Through all the twists and turns, Ferguson never understands (or rather, never is able to convince himself he understands) Madeleine. The history (of Madeleine, of Dolores, etc.) regresses too far for his eyes to penetrate. Unable to free himself from this convoluted plot and detached from reality, Ferguson imposes a narrative on Judy. He can’t figure out the mystery, so he might as well write his own answer. And the viewer accepts this to some degree because the story is resolution-deficient. Trapped staring through Ferguson’s gaze, escape is—depending on the specific viewer—to some extent preferable, even when it carries such gross implications.

The endgame of Ferguson’s gaze is sex. The male gaze conjures scenarios—no matter how fantastical—where legally-consensual5 sex occurs, and relates those scenarios with the real world in order to judge their plausibility, filtering those implausible scenarios from the gazer’s strategies. A plausible scenario would mean that Ferguson has successfully dissected her, inducting her motives, and—with them in hand—smooth-talked her into thinking that his motives overlap with hers. But since Ferguson cannot understand Judy, because he cannot relate fantasy with reality, he resorts to the truly outrageous step of realizing those fantastical scenarios and their absurd bargaining power disparities, molding Judy so that her [perceived] motives can be induced to comport with Ferguson’s desires. This decision fabricates the conscience-satisfying, superficially-consensual sex that ends Vertigo. Horrifically, the viewers’ interests are sympathetic to Ferguson’s, begging for plot resolution, but are then [hopefully] spoiled when they are confronted with the idea that their interests imply the exploitation of Judy. From beneath the comfort of 1950’s American entertainment, a violent man watches.

In interpreting the greater significance of Vertigo, I benefit again from viewing Hitchcock through Lynch’s rear window:

My childhood was elegant homes, tree-lined streets, the milkman, building backyard forts, droning airplanes, blue skies, picket fences, green grass, cherry trees. Middle America as it’s supposed to be. But on the cherry tree there’s this pitch oozing out – some black, some yellow, and millions of red ants crawling all over it. I discovered that if one looks a little closer at this beautiful world, there are always red ants underneath.6

Hitchcock views America somewhat from the outside. He picks a very particular part of the US, one where the histories of people who were not British is readily apparent in depictions of frontier life (and Native death). This choice primarily works to operate on the level of uncanny history, a history that few are equipped to read completely into their own history of America, but with pieces that all can recognize. It’s therefore both easy to dissociate Ferguson’s particular position from their own, while difficult to completely disentangle the silver screen from real life. Stewart’s roles prior to Vertigo included US everyman turned Congressman in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, aviator Charles Lindbergh in The Spirit of St. Louis, a cowboy in Winchester ’73, George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life. I cannot think of another actor who so embodied rich, moral American-ness during this time. Hitchcock then takes apart this rich, moral, American figure by finding within him obsession, formidable sexuality, and desperation. A bit of psychological trauma sets off (or reveals?) the ants in this cherry tree. More specifically, the bent of America is towards taking that which/who is not ours and assimilating them, without dealing with “underlying” issues.

I find it difficult to read Hitchcock as directing in so critical a fashion as I have just suggested, given the patent fetishism of Kim Novak’s characters. In that vein, I would echo the interpretation of American men above, but stop short of believing Hitchcock to be fully critical. For him, I don’t think the discomfort of Judy’s situation outweighs his fetish for Novak. While Vertigo is a unique instance of 1950’s filmmaking for its unsettling features and early integration of psychoanalysis, I’m not convinced of any allegations of intent on Hitchcock’s part. It very well may be that old Alfred was the astute critic I have made him to be, but it could equally (in my eyes) be the case that he was utterly obsessed with Novak. To resolve Vertigo’s interpretation would be to impose, for all but the most ardent individualist, an idea of its meaning absent context of its author. While I generally distance myself from arguments about authorial intent, I do not want to foreclose the possibility of its import to other viewers.

Footnotes

cf. The Wrong Man (1956)↩︎

Novak in ~Act 1~.↩︎

Cf. This comical image of a charity coin spinner, or how a gravity well may alter planetary orbits.↩︎

Note that this means thoughts become detached from external reality. When we understand that no person can diagnose another from anywhere but their own viewpoint firmly in the mainstream of productive society, it becomes clear that the usage of the word ‘reality’ is misleading. Reality does not exist—it is judged to exist—but always with psychology this judgment originates from the highly-educated professional class. Understanding what ‘external reality’ entails means Ferguson could both be “detached from external reality” and quite rational in both his and the viewers’ eyes. Hitchcock plays on this truth in many films. Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean somebody isn’t out to get you.↩︎

Otherwise, one would have no need for fantasizing.↩︎

Lynch, David and Rodley, Chris (2005). Lynch on Lynch (revised edition). New York: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22018-2.↩︎